Khiva, the ancient capital of Khorezm, is a village more than 2,500 years old and dominated today by a mosque, complete with a tiled minaret as thick as a chimney. This was built in the 19th century next to the historic caravanserai and schools (or madrasi) and protected by a well-preserved city wall. Silk Road tourists have seen similar settlements in Bukhara and Samarqand. Only here, everything is smaller, more clearly arranged, well-preserved, and rather untouched by the usual bazaar hustle and bustle of such tourist centers. The trading town on the old Silk Road is picturesque – or it was for as long as it could feed its inhabitants and guests from the alluvial deposits of the Amudarya River, which kept changing course, sometimes threatening to flood the city, only to recede so far from it that the oasis on the steppe it left behind could no longer produce enough food.

Forty kilometers away in the administrative center of Urgench, we sit in one of the typical huge Uzbek restaurants that open late in the morning and close very late at night – meeting places for families and friends, who joyfully greet and say goodbye to their constantly coming and going guests. Whole days pass effortlessly in this way. People meet, chat, do business, argue, and reconcile without having made prior arrangements. The later the evening, the sooner the tables are moved, the more exuberantly the guests tremble. That is the name of their dance; Lazgi means “to tremble.” It is this custom of dancing after dinner that has allowed this ancient dance to survive to this day.

In fact, it looks like electric shocks are running through the dancers, and one wonders why. Perhaps, one suspects, this trembling is an early cultural imitation of the seismic and volcanic activity of those ancient Paleolithic times when humans first settled on these fertile alluvial lands of the Amudarya, most of whose water is now used on cotton plantations. Thirsty cotton is the region’s main source of income, but is now causing the abundant water in the steppe-like Khorezm to dry up once again.

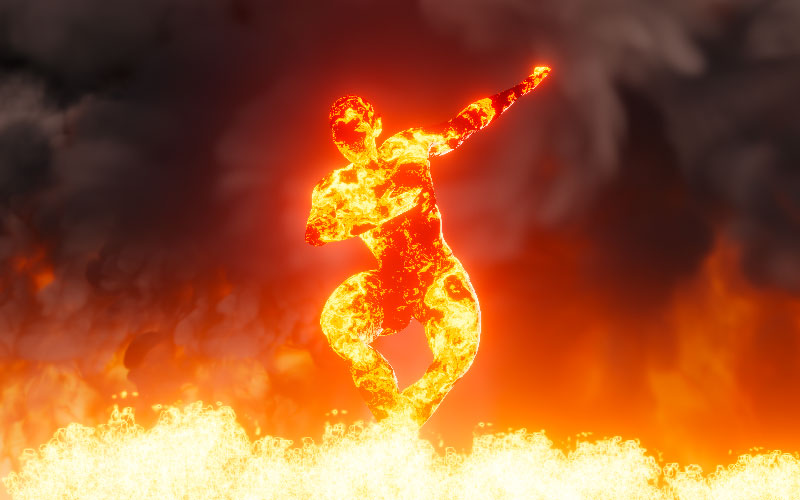

A second explanation for the trembling movements of Lazgi is as true as it is likely: It goes back to the Zoroastrian pre-Islamic fire cult. Commemorated by Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra is the more common name for the religion’s founder. Zoroastrians guard the eternal flame, worshipping it and the sun – even here in Khorezm, where the sun rose for the Parsis, as the Persians have been called since their flight from Islam.

Lazgi dance begins with a frozen posture. First, and hardly noticeably, the fingers tremble, then the hands, the arms, the shoulders, then the whole body. It looks as if the dancers are thawing out, as though they had been frozen by the winter or during the night, and now, with the beginning of spring or sunrise, new life is entering them. The sequence of fluttering fingers, bent joints, and trembling limbs becomes increasingly wild. All of this is structured in such a rhythmic complexity of head and limbs that it looks as if a smiling doll with seemingly broken bones were elegantly rising, shaken as if by an earthquake, and now becoming fire itself, as a result of the quake that sets its body ablaze like a flame.