In addition to the Mikhailovsky erTheatre, it is above all the Mariinsky, the first ballet ertheater in Saint Petersburg. This ertheater, too, no longer presents brilliant premieres, but dances the achievements of the past. The repertoire of Makhar Vaziev is still danced there, as are the ballets of the legendary Alexei Ratmansky – the choreographer who openly opposed Putin, protested against the war, and has now found a new home a comfortable distance away at the American Ballet erTheatre in New York. Even though Ratmansky’s work is still being shown in Saint Petersburg, his name is never mentioned on the program. Concealment is customary. The danger of being accused of propaganda by “foreign agents” is too great.

And this is now threatening Alexei Ratmansky, who spent two years reconstructing “The Pharaoh’s Daughter”, the first full-length ballet by Petipa in Russia. At the beginning of the Ukraine war, shortly before completion, Alexei and his wife Tatyana left the country. Since then, the name Toni Candelero, who completed the work in two months on behalf of the Mariinsky and describes himself as the author of the work, has been emblazoned under this work.

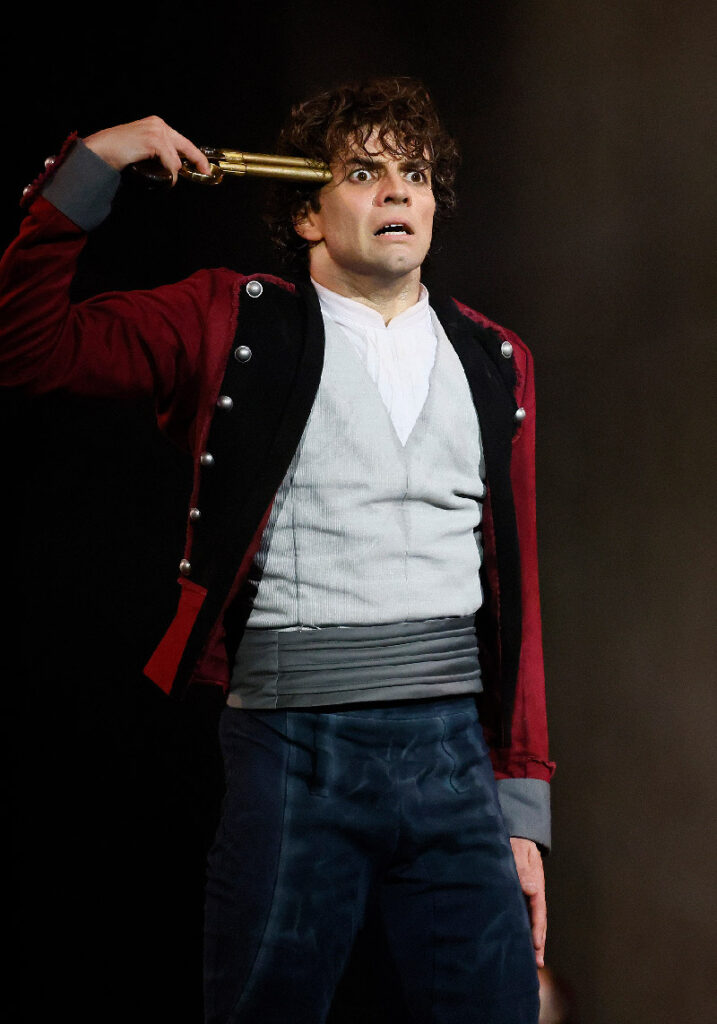

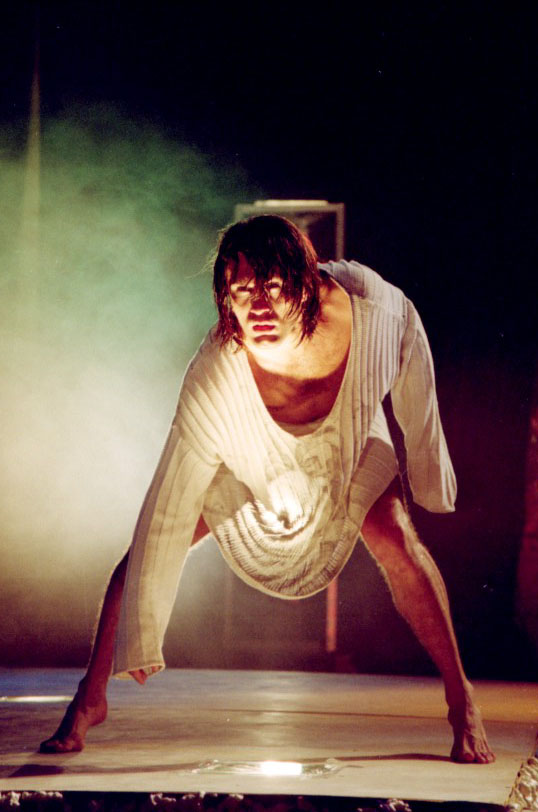

But it’s not the case, as you might think from my story, that everyone in the world is now creeping across the stage on Russian territory, hunched over. No,; a number of small, up-and-coming movements are underway, far away from Moscow. These include the work of individuals such as Olga Tsvetkova, who has founded a new dance academy in Saint Petersburg, or the ballets of Vladimir Varnava, who staged “Petrushka” to the music of Igor Stravinsky and the “Yaroslavna Eclipse” at the Mariinsky – full of sarcasm and grotesqueness. That was in 2017. Today, Varnava works mainly in ertheater together with directors such as Maxim Didenko and his musical “Run, Alisa, Run” at the Taganka erTheatre in Moscow, where the sentiment is firmly anti-Putin.

Vladimir Varnava’s last ballet at the Mariinsky erTheatre, “Yaroslavna Eclipse,” deserves special attention. The piece, with music by the avant-garde composer Boris Tishchenko, was first performed in 1974 at Leningrad’s Maly Opera House and was recognized at the time as being magnificent in its political and social message in the context of the ideological norms of the USSR. “Yaroslavna Eclipse” is like a response to Borodin’s opera “Prince Igor.” The choreographer Oleg Vinogradov, the director Yuri Lubimov, and the dancer Nikita Dolgushi contradicted the traditional material and had no sympathy for Prince Igor, who had overestimated his military strength and lost the battle against the Mongols and Tatars. “Yaroslavna Eclipse” openly condemns Igor’s complacency and pride. He started the war, he lost that war, and Igor’s actions brought terrible suffering to his people.