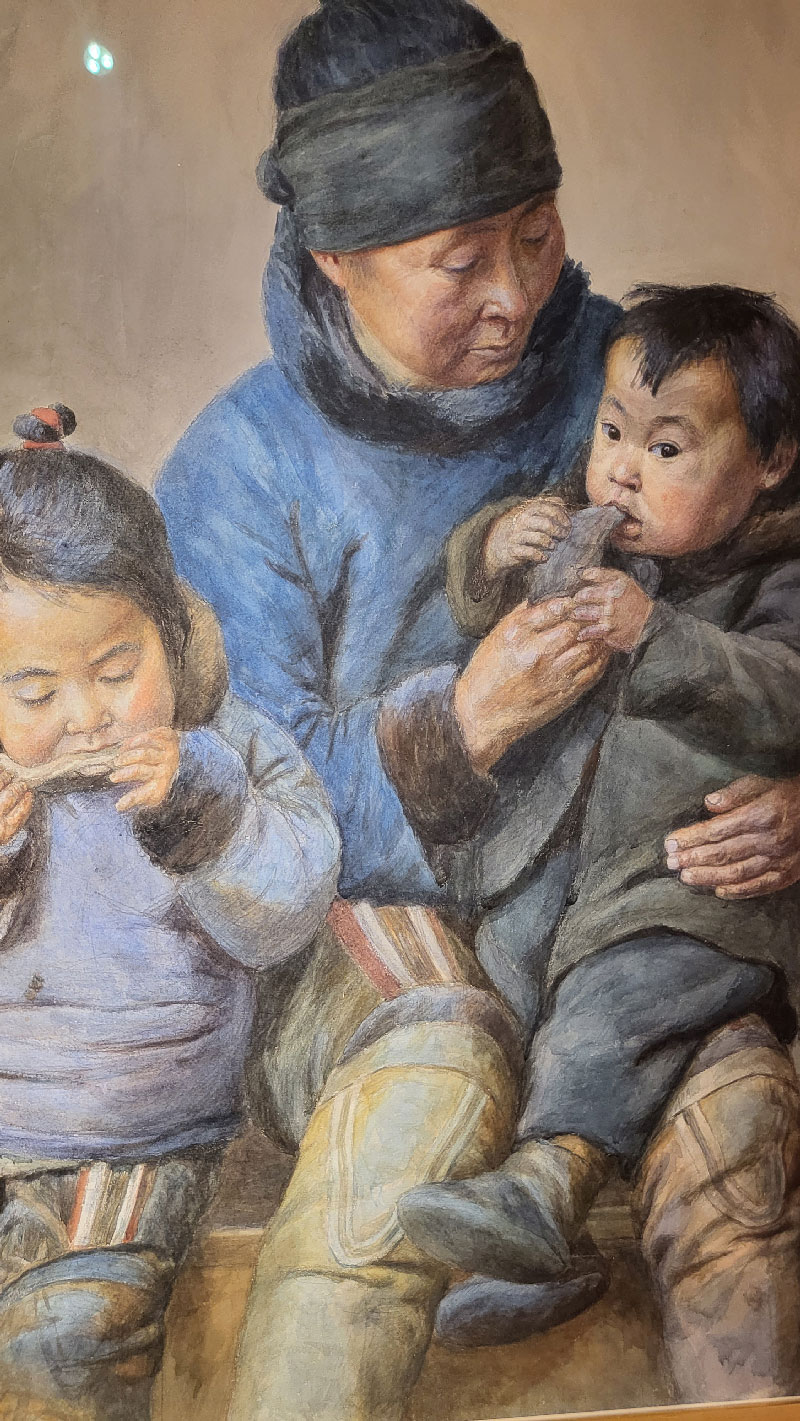

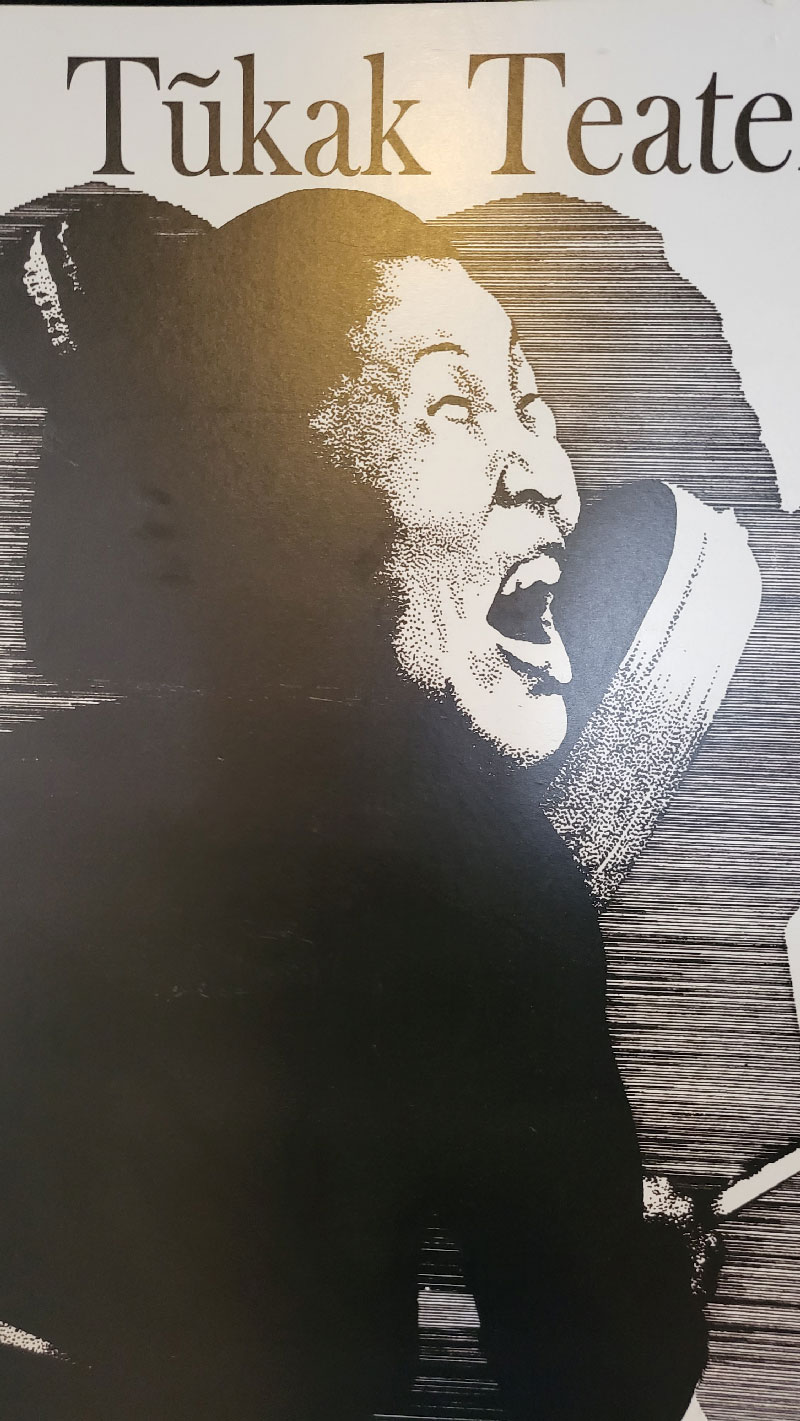

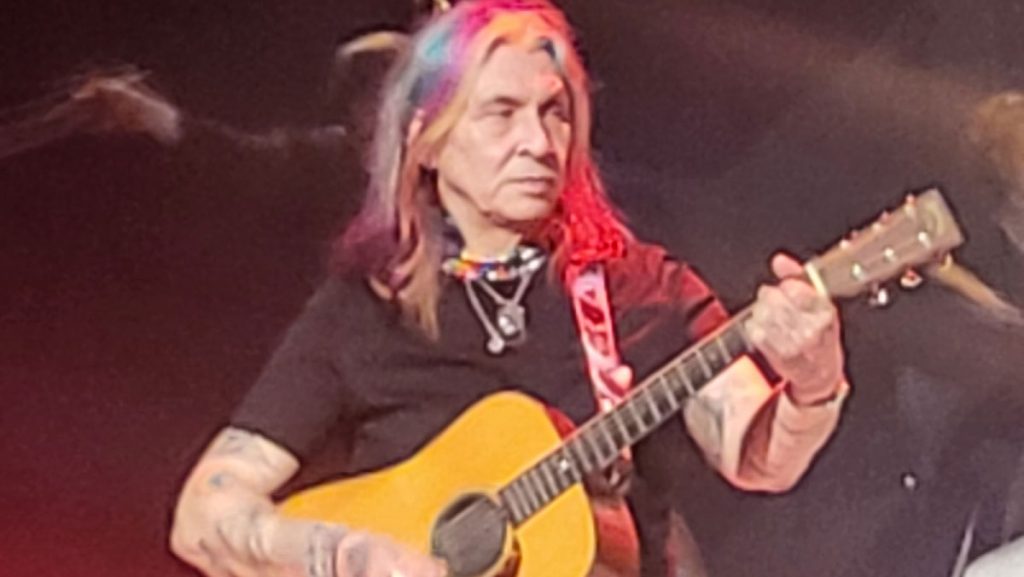

Since Greenland already has two national anthems, this song is now considered the unofficial third. Only the band Piitsukkut no longer exists. For the rock musical “Palasi” it is being covered by a younger generation. The audience are quick to jump out of their seats. The song of the rising sun is projected onto the wall, karaoke-style. And while the audience – well, about half of it (the other half doesn’t understand or speak Greenland’s language Kalaallisut) – sing along fervently, he enters the stage: Hans Peter Kleemann. Unmistakable, his long hair in rainbow colors, traditional Inuit tattoos, guitar – the last remaining member of the band, born in 1956 and devoted grandfather of two granddaughters: “I always say that grandparents should spoil the children while the parents should raise them.” He, too, is a child of his grandparents. He grew up in his mother’s childhood home on an island in northwestern Greenland. His grandmother brewed schnapps: “At night, when we heard a loud pop, we knew the bottle was ready to be drunk,” he recalls. And his grandfather’s brother taught him not to play on ice floes by pushing him off one into the freezing water. At school he was the only Greenlander among a pack of noisy Danes, was bullied, went to secondary school in the small town of Asiaat, and at a party there met the older musician Maasi Lynge, who would go on to become the lead singer of Piitsukkut. “The secondary school had a curfew in the evenings. When the band had a gig, I would jump out the window and run to the community center to hear them play,” he says. He followed his new idol Maasi Lynge to Qaqortoq, way down in the south of Greenland. There, it was always party time. The Maoist-influenced Inuit Ataqatigiit party had also just been founded and organized a summer camp in Aasivik with the current mastermind behind the “Palasi” production. Music producer Karsten Sommer, born in Strasbourg and Danish by passport, also joined the band. His record label ULO Records led Piitsukkut to success. Karsten Sommer likes to talk about this legendary summer camp at the traditional gathering place of the Inuit, which was used to store their winter supplies. In 1979, it became a place to also “stock up on winter supplies for the brain,” he says. With music that was political and, above all, angry enough to ensure the land would no longer be left to the Danes.

Piitsukkut’s old song “Palasi” (“Priest”) begins like this: “We heard one who didn’t speak our language. He stretched out his hands and waited for ours.” The rest of the song relentlessly criticizes the church for its role in colonizing the Inuit: as a clash of cultures. This clash was not over yet. On one side were Hans Peter Kleemann and his rebellious fellow musicians, who called their art “brand new political anti-colonialist art in Greenland.” On the other side was the church, which protested vehemently and succeeded, with the help of state pressure, in getting KNR, the only radio station in Nuuk, to stop playing the song for two years. Now the song has lent its title to a whole rock musical.

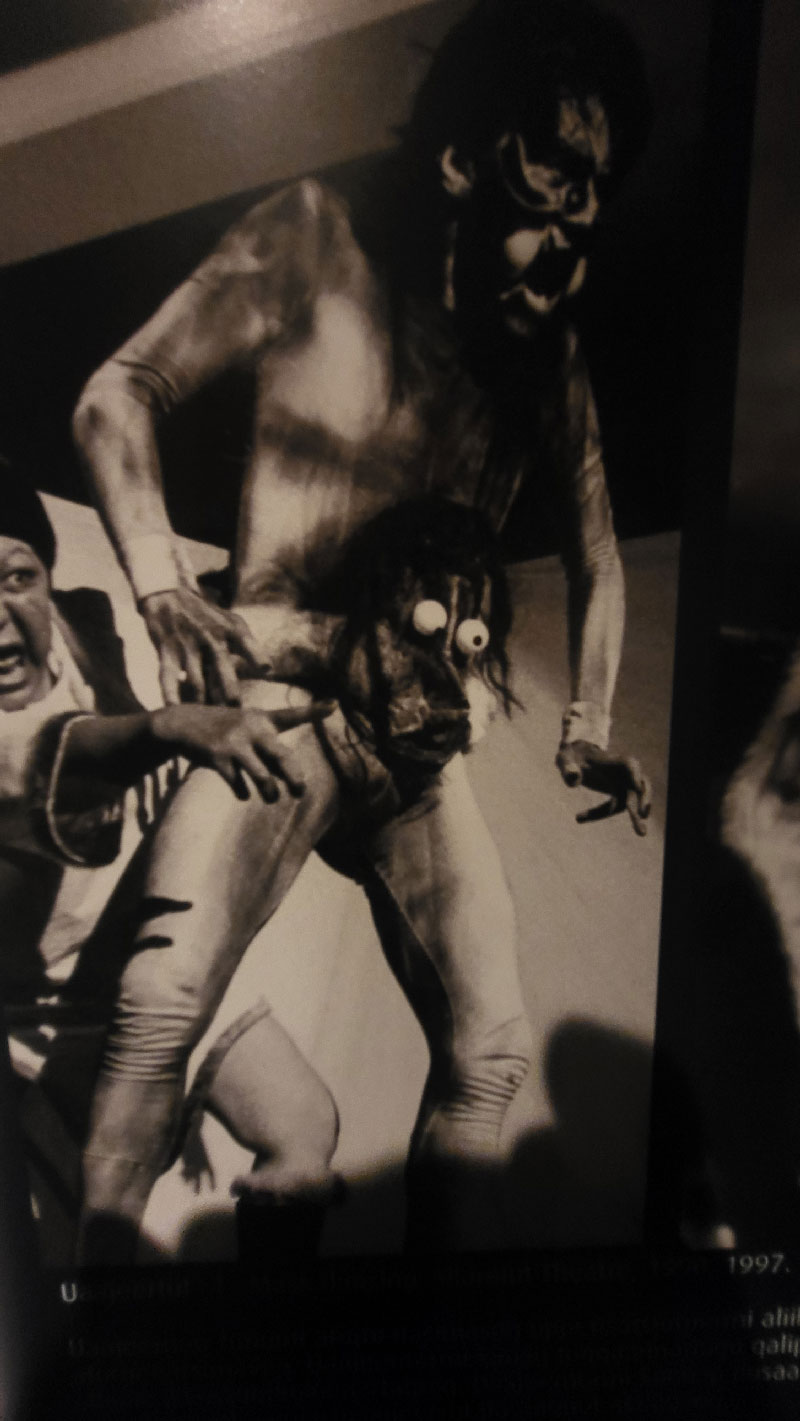

Its plot primarily consists of trivializing the very popular Greenlandic motif of the struggle of the shaman against the preacher, of faith based around nature versus monotheism, as if it were a battle of faith at eye level. This is also what Greenland’s great actress and playwright Makka Kleist does, whose duo “The Shaman and the Priest,” also loosely based on Hans Egede’s mission diaries and personal memories of the Inuit, was staged by Hanne Trap Friis as a chamber play in Aarhus. Hans Egede apparently acts as a collective trauma. In “Palasi,” an Inuit choir performs on a video screen that obscures the orchestra. The orchestra is the Arktisk Filharmoni all the way from Tromsø. In the center of the stage stands a replica of the statue of Hans Egede – “Come to Daddy” is written on its pedestal, as if spraypainted. The climax follows the erection of the monument of this Protestant missionary worker made of papier mâché – the blowing up of the monument, simulated by lighting and acoustic effects and accompanied by the song “The Sun” quoted above.