Thanks for the meetings and cooperation to the

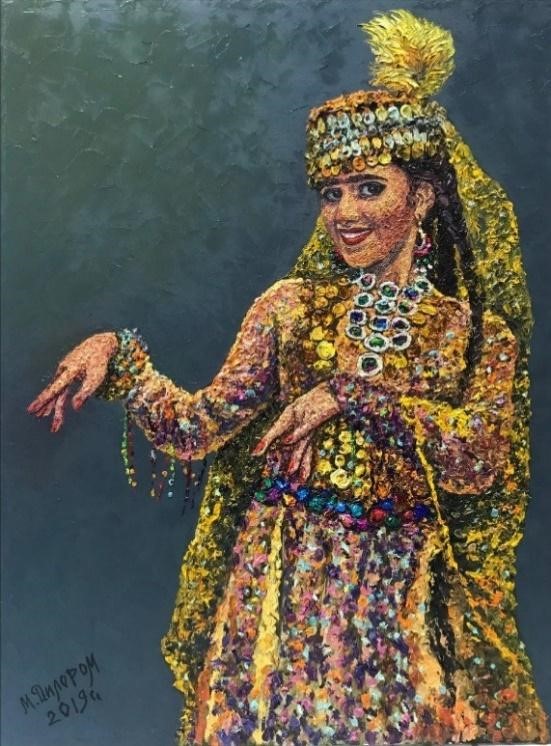

dancers and choreographers

Gavhar Matyokubova (Uzbekistan), Dilnoza Ortigova (Uzbekistan), Aguibou Sanou/Tamadia Dance Company (Burkina Faso), Serge Aimé Coulibaly/Faso Dance Theatre (Burkina Faso), Stefany Ursula Yamoah/ National Dance Company (Ghana), Tchina Ndjidda (Cameroon), Ochai Ogaba/Mud Art Company (Nigeria), Chef Kossi (Togo), Anamaria Klajnscek (Slovenia), Magi Serra (Spain), Irina Demina (Germany), Julek Kreutzer (Germany), Mariko Koh (Germany), Chihiro Araki (Germany), Qadira Oechsle-Ali (Germany), Cordelia Eleonore Lange (Germany), Maria Walser (Germany), Viktória Kőhalmi (Germany), Ghazal Ramz (Germany), Anne Mareike-Hess (Germany), Neta Henik (Isreal/Germany), Sho Nakasatomi (Germany), Zumrad Mukhrimova (Netherlands/Uzbekistan), Xchel Mendoza Hermández (Germany), Lea Martini (Germany), Katharina Maschenka Horn (Germany), Zula Lemes (Germany), Manto Nosti (Greece), Filio Louvari (Greece), Nir de Volff (Germany), Anna Demiclova/Urban Forest Echo Theatre (Russia/Germany), Kasia Wolinska (Germany)

Composers and musicians

Otabek Ròzmetov (Uzbekistan), César B. (Germany), Midori Hirano aka MimiKof (Germany), Alejandra Cárdenas Pacheco aka Ale Hop (Germany), Mauricio Takara (Brazil/Germany)

Costume designers

Carolin Schoggs (Germany), Mascha Mihoa Bischof (Germany), Justyna Gmitrzuk (Germany), Lauren Steel (Germany)

Dramaturges

Diana Liu (Germany), Astrid Schenka (Germany), Thomas Schaupp (Germany), Foteini Micheli (Germany), Klara Kroymann (Germany), Maja Zimmermann (Germany), Nadine Vollmer (Germany), Ioanna Valsamidou (Greece), Helene Varoupolou (Greece)

Live Audiovisual Artists and VJs

KALMA (Germany), Claire Fristot aka A_li_ce (Germany)

Scenographers

Michi Muchina (Germany), Lena Loy (Germany), Cristina Nyffeler (Germany), Jacob Blazejczak (Germany)

Lighting designers

Emilio Checa (Germany), Matthias Singer (Germany)

Visual artists

Martin Kaltwasser (1965 – 2022) (Germany), Simone Zaugg (Switzerland)

Lazgi dance teachers

Malika Khaidarova (Uzbekistan), Katja Hillebrand (Switzerland), Zumrad Mukhrimova (Netherlands, Uzbekistan)