ARIMITSU 2015

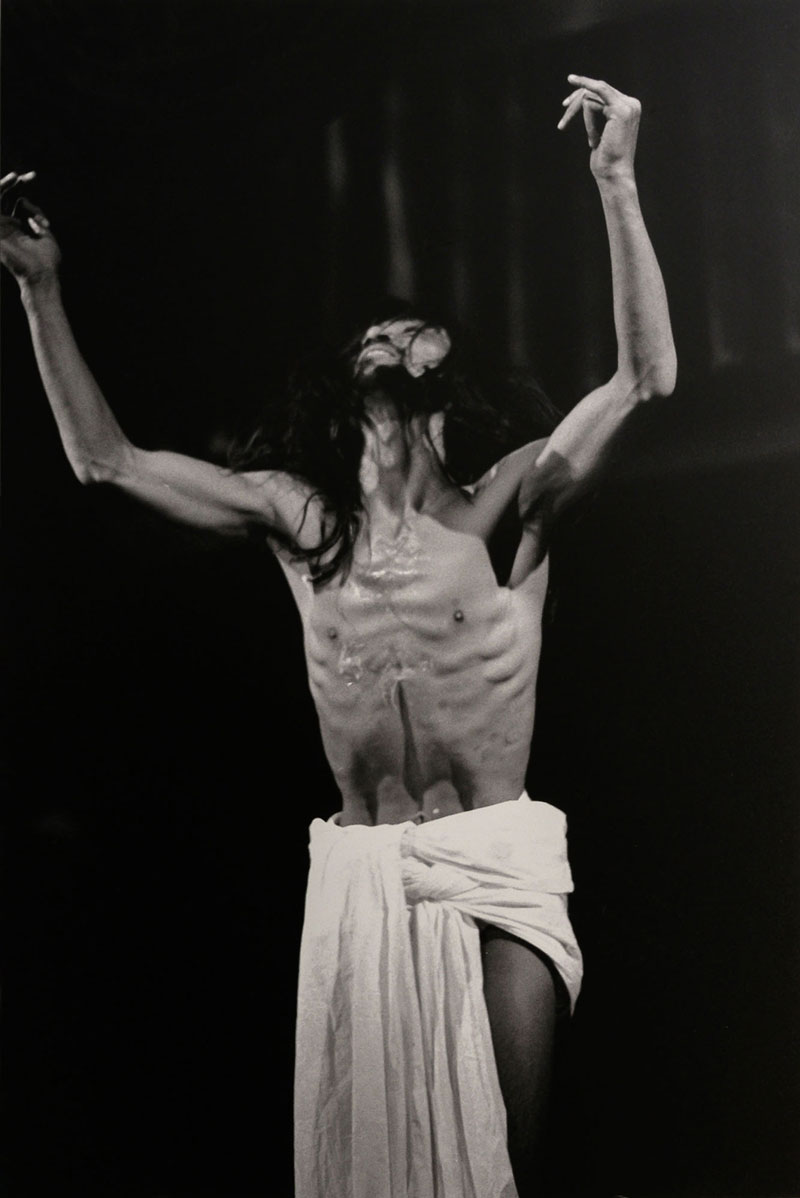

Michio Arimitsu, From Voodoo to Butoh. Katherine

Dunham, Hijikata Tatsumi, and Trajal Harrell’s

Transcultural Refashioning of ‘Blackness’, publ. von /

published by MoMA, 2015

Aleida Assmann, Der Körper als Medium des individuellen,

kollektiven und kulturellen Gedächtnisses,

in: Journal der Künste 12, 2020

AUSST. KAT. / EXH. CAT. BREMEN 2017

Der Blinde Fleck. Bremen und die Kunst der Kolonialzeit

(Ausst. Kat. / Exh. cat. Kunsthalle Bremen), Bremen 2017

AUSST. KAT. / EXH. CAT. MINNEAPOLIS 2011

Eiko & Koma. Time Is Not Even, Space Is Not

Empty (Ausst. Kat. / Exh. cat. Walker Art Center,

Minneapolis), Minneapolis 2011

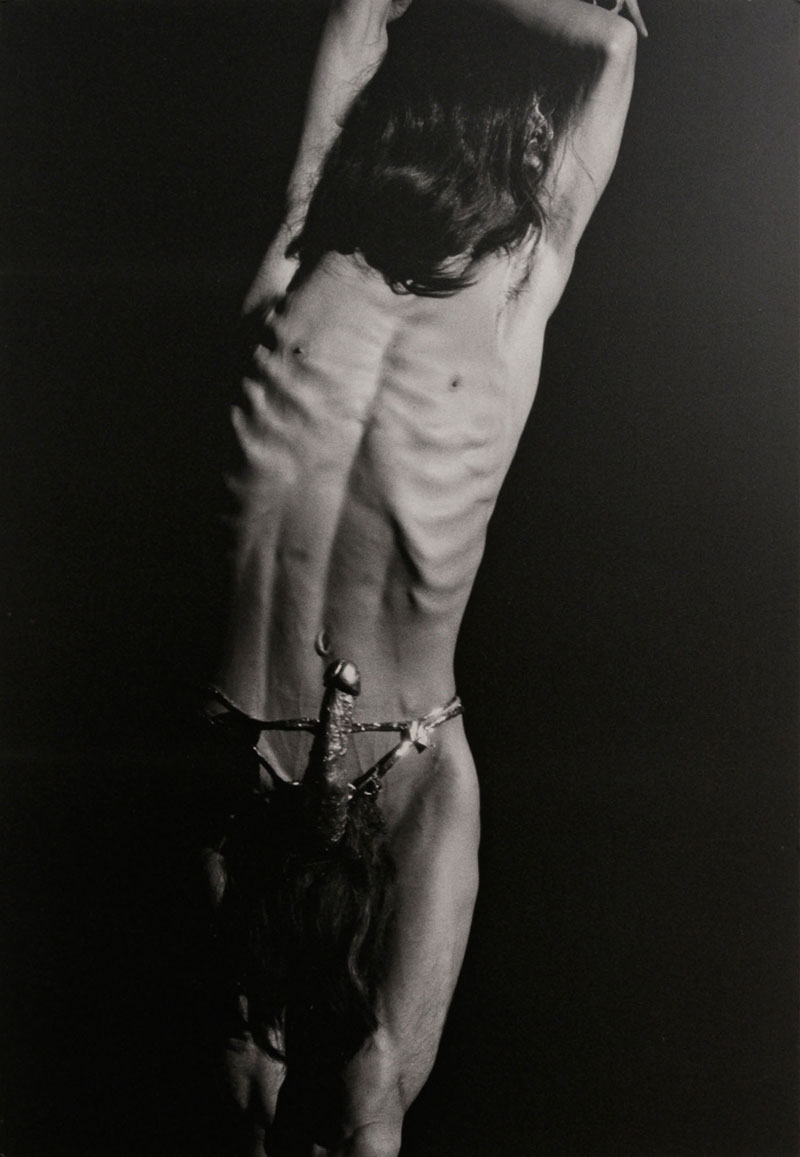

AUSST. KAT. WIEN / EXH. CAT. VIENN A 2016

Provoke. Between Protest and Performance – Photography

in Japan 1960/1975, hg. von / ed. by

Matthew S. Witkovsky und / and Diane Dufour

(Ausst. Kat. / Exh. cat. Albertina, Wien u. a. / Vienna

et al.), Göttingen 2016

AUSST. KAT. / EXH. CAT. MUNCHEN 2018

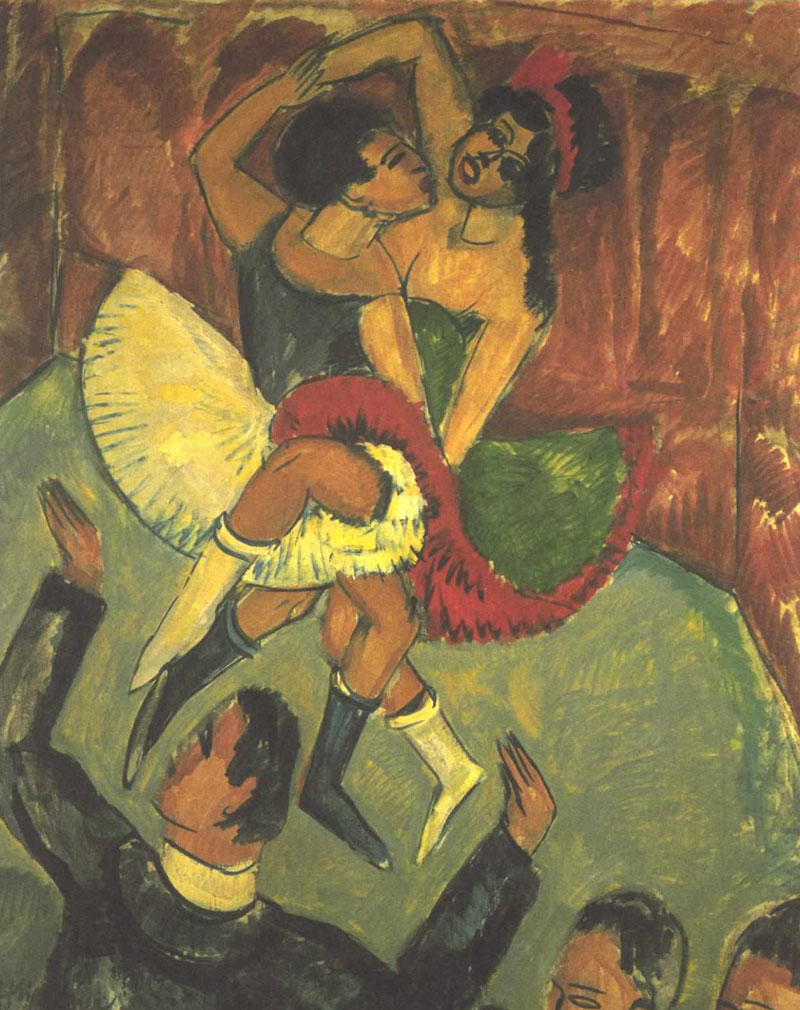

Kirchners Kosmos: Der Tanz, hg. von / edited by

Brigitte Schad (Ausst. Kat. / Exh. cat.

Kirchner HAUS Aschaffenburg e.V.), München 2018

AUSST. KAT. / EXH. CAT. MUNCHEN 2021

Kirchner und Nolde. Expressionismus und Kolonialismus

(Ausst. Kat. / Exh. cat. SMK – Statens Museum for Kunst, Kopenhagen

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Brücke-Museum, Berlin), München 2021

BAIRD/CANDELARIO 2020

Bruce Baird und / and Rosemary Candelario

(Hg. / eds.), The Routledge Companion to Butoh

Performance,

London 2020

COHEN (2022)

Matthew Isaac Cohen, On the Way to Asia. Exoticism,

Itinerancy and Self-Fashioning in the Making

of Central European Modern Dance, in: Re-writing

Dance Modernism. Networks / Prze-pisać taneczny

modernizm. Sieci, hg. von / edited by Julia Hoczyk

und / and Wojciech Kliczyk, Warschau / Warsaw

(voraussichtlich / forthcoming 2022)

CONVERSATION 2016

Conversation. With Trajal Harrell, Eiko Otake, and

Sam Miller. Moderated by Lydia Bell and Judy Hussie-Taylor,

in: A Body in Places, hg. von / edited by

Danspace Project, New York 2016

GRISEBACH 1997

Lothar Grisebach (Hg. / ed.), Ernst Ludwig Kirchners

Davoser Tagebuch, Ostfildern 1997

KIRCHNER BRIEFWECHSEL

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Der gesamte Briefwechsel,

bearb. und hg. von / with an essay and edited by

Hans Delfs, Bd. / vol. 2, Zürich 2010

KIRCHNER NEU DENKEN

Annick Haldemann Wolfgang Henze und / and Martina Nommsen

(Hg. von / eds.) Kirchner Neu Denken, Zur Kirchner Tagung 2018,

München 2020

KRAVAGNA 2017

Christian Kravagna, Transmoderne. Eine Kunstgeschichte

des Kontakts, Berlin 2017

KRAVAGNA (2022)

Christian Kravagna, Transmodern: An Art History of

Contact, 1920–1960, Manchester (voraussichtlich /

forthcoming 2022)

MANNING 2006

Susan Manning, Ecstasy and the Demon. The Dances

of Mary Wigman, 2. Aufl. / 2d. ed. Minneapolis 2006

NAKAHIRA 1968

Takuma Nakahira, Komedi kyōki no bigaku no

Paradokusu – Hosoe Eikō ten „Totetsumonaku

higekitekina kigeki“ (The Paradox of a Mad Aesthetic

– Hosoe Eikō’s Photo Exhibition ‘Extravagantly

Tragic’), in: Nihon Dokusho Shimbun, 15.4.1968

PAGÈS 2015

Sylviane Pagès, Le butô en France. Malentendus et

fascination, Paris 2015

PETER 1997

Frank-Manuel Peter (Hg. / ed.), Der Tänzer Harald

Kreutzberg, Köln / Cologne 1997

PETER 2019

Frank-Manuel Peter, „Ein Mittelpunkt der modernen

Tanzkultur, ein mächtiger Anziehungspunkt

für aufstrebende Talente … “. Harald Kreutzberg,

Yvonne Georgi und der Bühnentanz in Hannover

zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik, in: Ausdruckstanz

und Bauhausbühne, hg. von / edited by Hubertus

Adam und / and Sally Schöne (Ausst-Kat. / Exh. cat.

Museum August Kestner, Hannover), Petersberg

2019

SORELL 1986

Walter Sorell, Mary Wigman. Ein Vermächtnis,

Wilhelmshaven 1986

TAKASHI 2015

Morishita Takashi, Hijikata Tatsumi’s Notational

Butoh. An Innovational Method for Butoh Creation,

Tokio / Tokyo 2015

WELSCH 2017

Wolfgang Welsch, Transkulturalität. Realität,

Geschichte, Aufgabe, Wien / Vienna 201

WIGMAN UN DATIERT / UN DATED B

Mary Wigman, Indien – Tanz, Typoskript, undatiert /

undated typescript, Ordner/Archivnummer / folder

1392, Nachlass / Estate of Mary Wigman, Archiv der

Akademie der Künste Berlin