Such is the high regard with which they have been held in cultural circles that the Japanese government designated both Yachiyo V and her grandmother, Yachiyo IV as National Living Treasures in acknowledgement of their outstanding contributions to the nation’s cultural repository, thereby joining an eminent coterie of traditional performing artists officially recognized as guardians of important intangible cultural properties. As of 2023, some 1400 individuals have been awarded with this life-long title. Honorees receive a one-time stipend from the Japanese government in an attempt to help them focus on their art. By accolading these individual practitioners, the government aspires to preserve and transmit indigenous artforms to future generations; not only are they honoured as talented personalities per se but equally as repositories of cultural knowledge and a savoir-faire that might otherwise die out.

Restraint

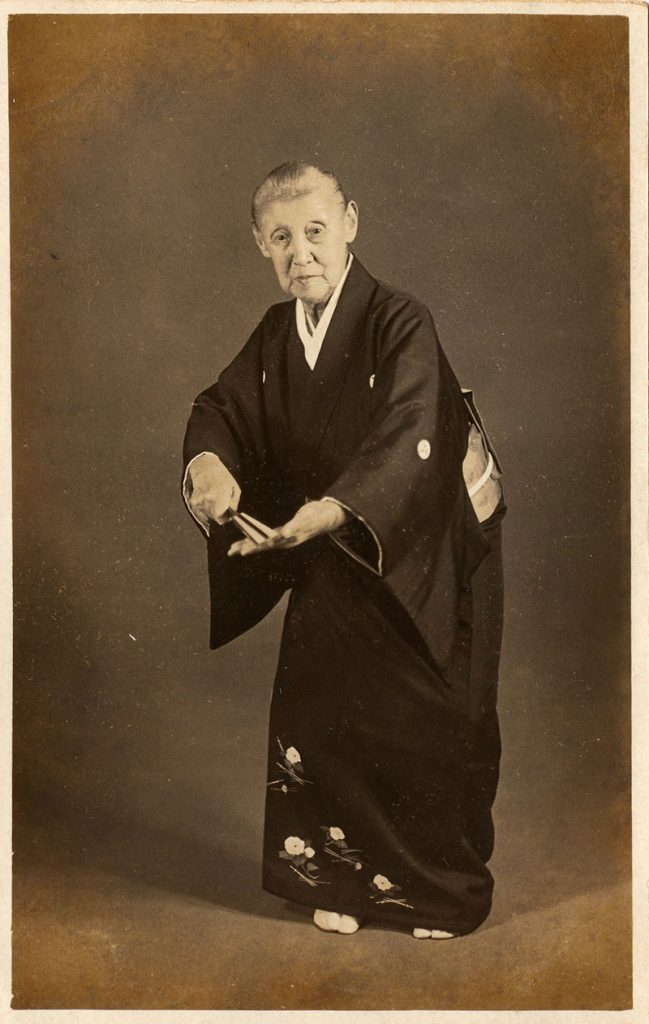

Kyomai has constantly been embedded in Kyoto’s communal fabric and notably linked with the Gion quarter, the epicentre of the city’s bustling nightlife. Ever since the Edo period, Gion has been a colourful entertainment quarter where Kyotoites gather to partake of local delicacies and alcoholic beverages and enjoy being entertained by geiko, the term for geisha in the Kyoto dialect. Like the denizens of Japan’s erstwhile capital, Kyomai practitioners don’t gravitate toward explicit expression. Rather, they tend to quietly convey their feelings, at once embodying womanly tenacity and feminine tenderness. With simple, unpretentious movements, their dance is subtly suggestive. Fundamentally, it involves the dancer properly applying strength to her abdomen, thereby anchoring the body’s centre of gravity and enabling the upper part of her body to eloquently trace lines and sculpt the air. While a Kyomai dancer must harmoniously synchronise the movements of her arms, hands, feet and neck, the dance’s essence lies in her portraying her most profound thoughts and emotions with a minimum of means and without resorting to clichéd facial expressions or stereotypical gestures or poses.

Urban Myth

The enduring urban myth that Geisha are linked with the sex industry has been fuelled by the widespread use of the term “geesha girl” which came into vogue during the immediate post-war years as Allied sailors and military personnel first came into contact with Japanese life. Bandied about ever since, it morphed into a sweeping generalisation about female workers in Japan’s nightlife sector, ultimately becoming a byword for a prostitute or a cabaret hostess.

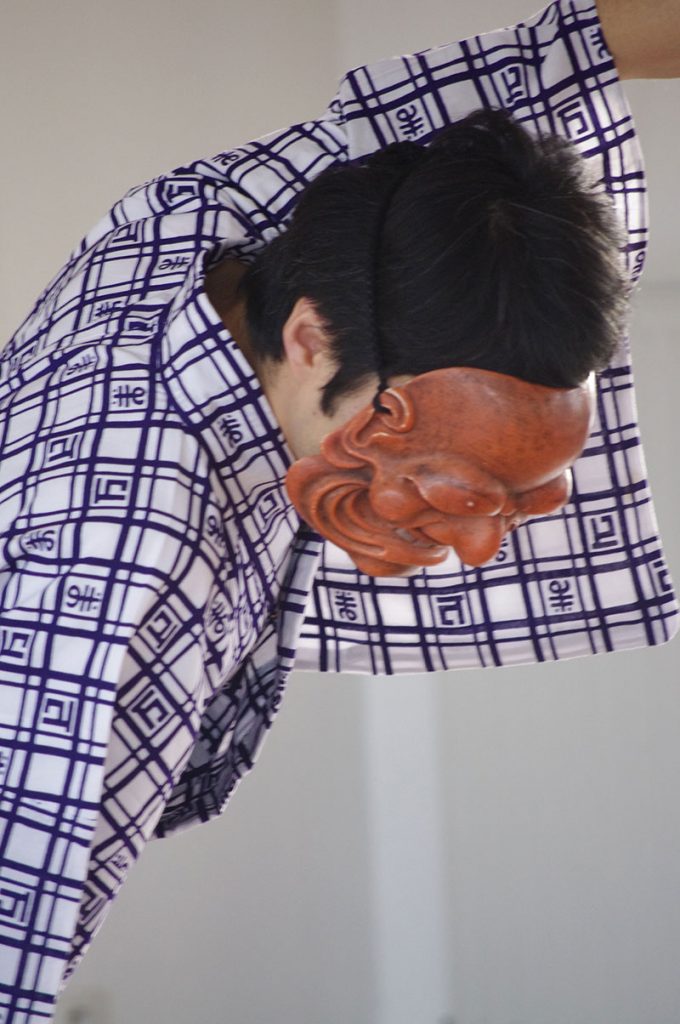

Written with the kanjis for art 芸 (gei) and person者,(sha) the compound term Geisha literally means a person endowed with artistic skills. As the term is currently understood and used in Japan, it denotes a highly skilled professional female entertainer trained in a broad spectrum of Japanese traditional arts, as well as the art of convivial repartee. Interestingly, some of the earliest known records of Geishas – from the early 17th century – refer to taiko-mochi (literally, drum bearers) who were actually men. Essentially, they were court jesters, musicians, and raconteurs who entertained the nobility. Some twenty-years later, the first female geisha appeared on the scene, and before the end of the century they were to dominate the profession. Whilst it is well beyond the scope of this article to navigate the intricate history of geishas and courtesans over the ensuing centuries, suffice to say that the notion that geisha are synonymous with bar hostesses is a misconception; her primary task is to delight her clients, or audience as the case may be, through her art and her wit.

Onerous Apprenticeship

By all accounts, the number of young Japanese women currently interested in becoming a geisha has been dwindling for some time. Notwithstanding their tremendous cultural significance, the future of this highly respected profession remains an open question. Little wonder, for becoming a full-fledged geisha today involves long years of arduous training, following a strict disciplinary regime. Any young woman aspiring to become a geisha must initially undertake an apprenticeship which takes about five years to complete, during which time she will acquire all the necessary skills for the role, inter alia, song, dance, musical accompaniment, the art of conversation as well as the requisite hosting finesse expected in a social setting. The aspiring maiko [literally, a dancing child] must first apply to an okiya [lodging house/drinking establishment] run by a matriarchal figure referred to as an oka-san [mother] – often themselves retired geishas – who will take the fledgling under her wings, and tutor her in the wide range of skills required to entertain her future guests as well as in all the intricacies of proper etiquette. The maiko has to live in the okiya with which she is affiliated, and it is the oka-san who will handle all her apprentice’s engagements and cover any expenses pertaining to her accommodation and daily needs, as well as supplying her with kimonos and the various sartorial accoutrements. With the exception of a small monthly allowance, any earnings the maiko might make will go directly to the owner of the okiya. The maiko is unable to earn an income until such time as all her debts to the okiya have been cleared. The oka-san, for her part, will fund the maiko’s training in the traditional arts during her apprenticeship.

In the past, a geisha’s fee was calculated according to the time it took an incense stick to burn. They have kept up with the times, however, and now it is simply calculated by the hour. A geisha’s earnings are contingent upon her popularity and how frequently she works entertaining guests at the ochaya [tea-house] with which she is affiliated. On occasion, they also perform on stage for the general public or at Kyoto’s seasonal festivals. Once a geisha has established herself, she may decide to move out of the okiya and live on her own. Geisha can and actually do perform well into their eighties or nineties, though there is an expectation that they continue to train regularly.