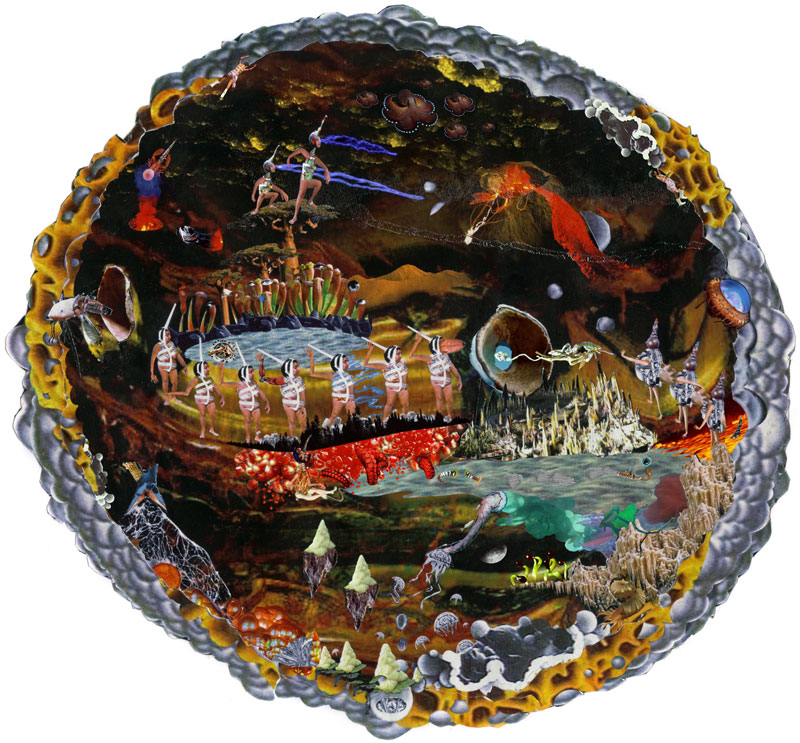

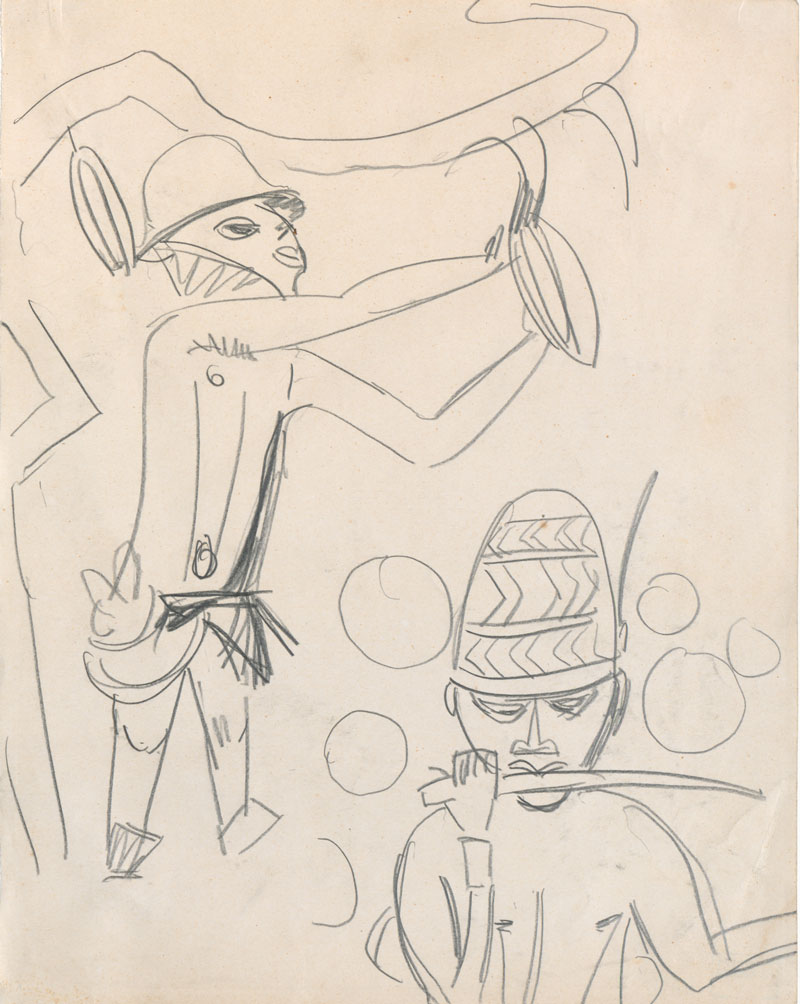

Modernism would be inconceivable without the interplay of inspiration and appropriation, any by implication the global groove of art, dance, performance, and protest. From a historical perspective, the German expressionist painter Ernst-Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) was from an early stage enthusiastic not only about non-European cultures, but also for dance. This very intersection was precisely where the avant-garde found its starting point: in movements from elsewhere.

Performance and Protest: From Ernst-Ludwig Kirchner to Kazuo Ohno

Dance enables us to sensorially experience how artistic globalisation processes and transcultural thinking have invariably been the norm. In 2021, at Essen’s Folkwang Museum, Marietta Piekenbrock, curator of the exceptional exhibition Global Groove. Dance, Art, Performance and Protest, in conjunction with Brygida Ochaim, went in search of concrete manifestations of such encounters between Western and Oriental avant-gardes. Who were ––and continue to be––the essentially transnational ambassadors at the dawn of the 20th century? Beginning with Mary Wigman and Kazuo Ohno in the past, to Boris Charmatz and the artist duo Eiko & Koma in the present, these Western and Japanese protagonists were and remain instrumental in a cross-cultural differentiation of modernism and postmodernism.