They are also concerned with a phobia – the phobia of the foreign. This can mean people from other cultures or equally those with a different faith, a different order, different laws. Phobias become especially interesting when they turn against our own interests. When men develop a phobia of the male body, this is not based on a biological protective mechanism, but is a culturally bred fear that ensures competition among men. Especially in the Americas, there exists a deep-rooted phobia of communists, socialists, and anarchists – although these forms of organization were and are commonplace among the original peoples, e.g., in Oxaca in southern Mexico, even in times when capitalism as such did not yet exist.

For Avendaño, this phobia affects two fundamental factors above all: our own bodies and the territory that surrounds them. My country, my body – both insist on the right to integrity. Both are to be protected. What was once protected in the community is now protected by law. If the executive and political branches are able to do so, they also protect the body and territory from the community.

Avendaño is convinced that “there is a mechanism for the control of bodies that Michel Foucault called the ‘microphysics of power’. The body and its extension, the territory, are both defended. So there is resistance. It’s important to me to also conversely recognize our own bodies as an extension of the physical territory. Others want to have power over both,” he says.

“Land and liberty,” Emiliano Zapata shouted in 1910, when he took up arms to demand rights for the indigenous peoples at the time of the Mexican Revolution. In his time, there was no democracy, no dialogue, and no other way out. Little has changed with regard to their situation – not even in 1994, when the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada stirred hopes among Mexican technocrats and business leaders of no longer being on the threshold to the “first world,” although people in the cities, but especially in rural areas, continued to struggle with extreme poverty and legal inequality.

The Mexican Revolution of 1910 did some things for the better, however: the protection of farmers, a right to land for sowing and harvesting, usufruct, a right that offered protection from rich landowners. Nevertheless, all of these reforms did little to help indigenous peoples. 1994, the year the FTA was signed, also saw the emergence of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, which would actively spotlight indigenous peoples, their situation, their needs, and their demands for at least another decade. There is no question that Avendaño sympathizes with this movement, which has shown him one thing above all, namely that no one is alone:

“Communist practices prevail in the communities of Oaxaca. Because of their perspective on land ownership, the inhabitants have always been anti-capitalist. There is no land ownership in the 570 municipalities of Oaxaca: Property is usually communal, very pragmatically out of resistance toward the large landowners,” he says.

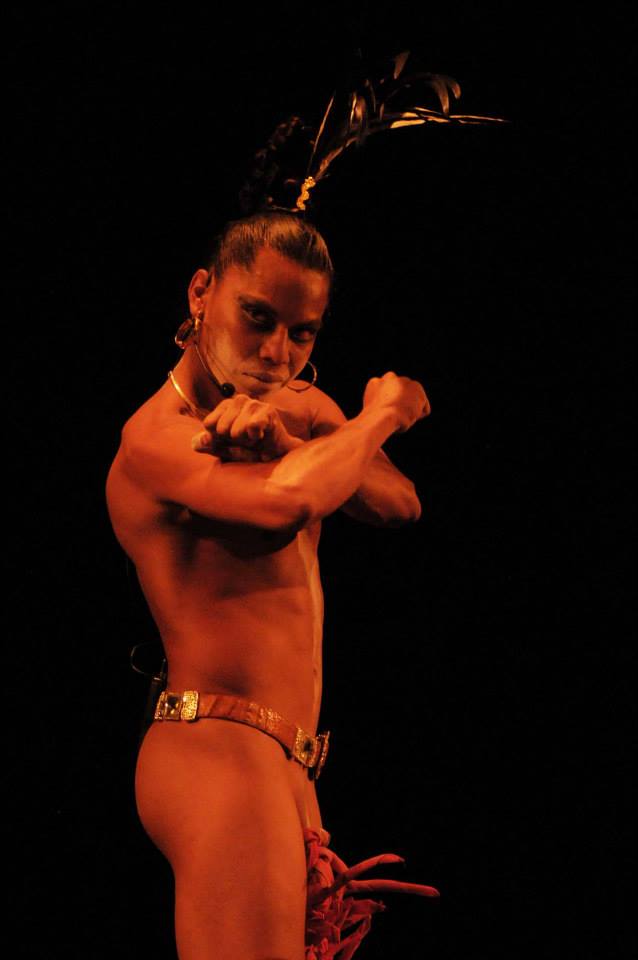

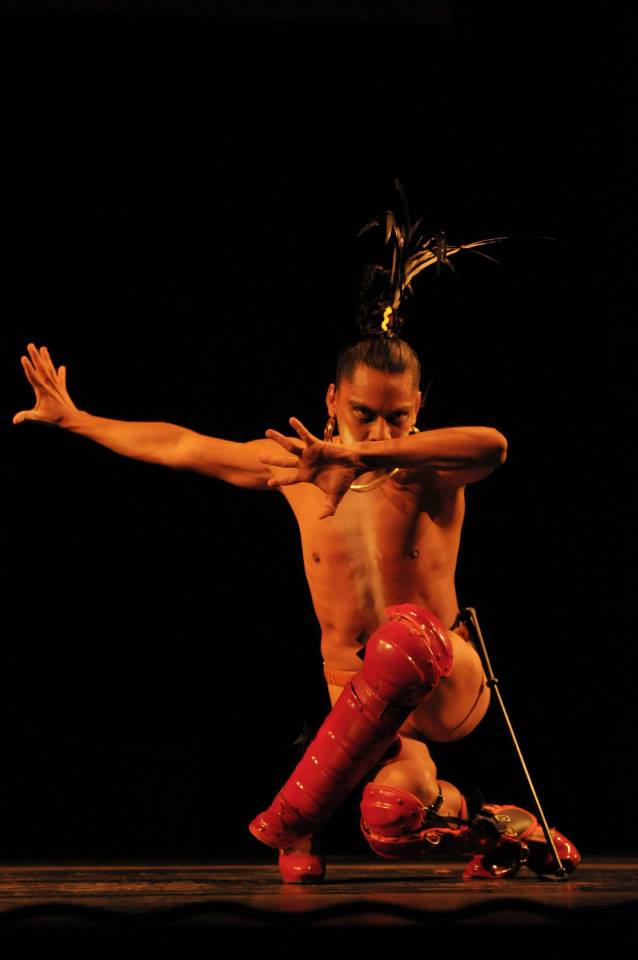

Just as a territory can belong to a municipality that will defend it, so, too, does the body need protection. In the theater, the entity offering protection is the stage. Even in his solo shows, Avendaño works collectively and cooperatively. That’s how he learned to do things in the community he comes from. No one is alone unless there is a power that drives them apart, a power that sows discord, that separates people, imprisons them, chases them away. Choreography, for Avendaño, is space and a form of resistance rolled into one. Collective body movements meet art and sound. Everyone on stage faces public discussion and debate. This is the ideal.

But even a community is only a singular entity; it cannot live without the others, without being protected by and from others. A territory, even if it is simply a stage, can never be protected by just one ensemble – only the audience can do so. But it is the tradition itself of having a theater at all that leads to our protecting it. “No theater, no resistance, can be financed only by those who perform or resist,” Avendaño says. “It seems to me that it is a fundamental mistake to think that a territory, a theater, a community can be protected by the community itself.” Emiliano Zapata already knew this in 1910.

Avendaño’s notebooks and scripts are full of thoughts like this. For him, every step on stage, the figures of each dance, however contemporary they may be, refer to rootedness and identity. His notations include phrases like, “You go on stage to claim your place, to claim what belongs to you and is yours.”