Voguing, Butoh, postmodernism – Trajal Harrell and his people are shaking up gender roles and rewriting dance history. In doing so, he touches a nerve of our time.

When Trajal Harrell heard that the critics’ jury of “tanz” magazine had voted him “Dancer of the Year 2018,” he thought it was a joke at first. He had never thought of himself as a great dancer.

“My cousins always said I was a bad dancer. Also when I came up in New York I was very different from most of the dancers. So it was very surprising that I was chosen as Dancer of the Year and not Choreographer of the Year.”

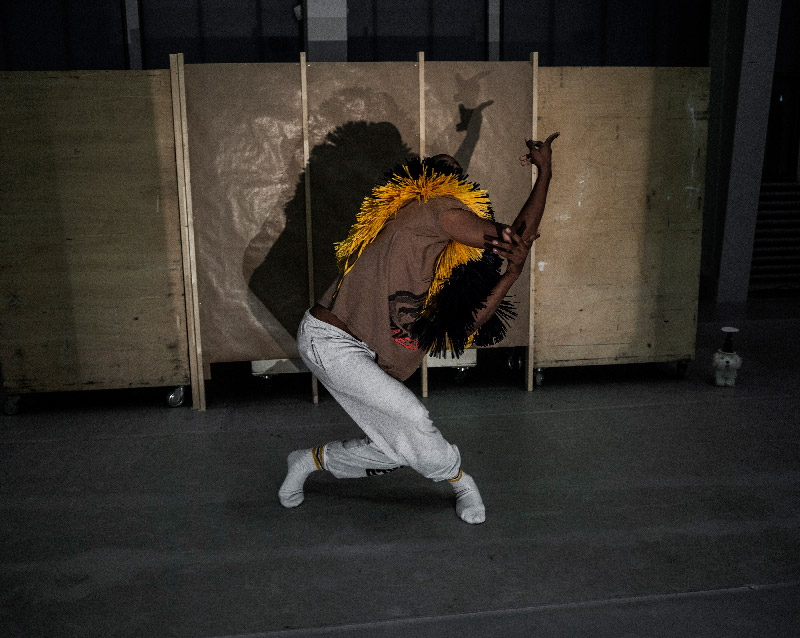

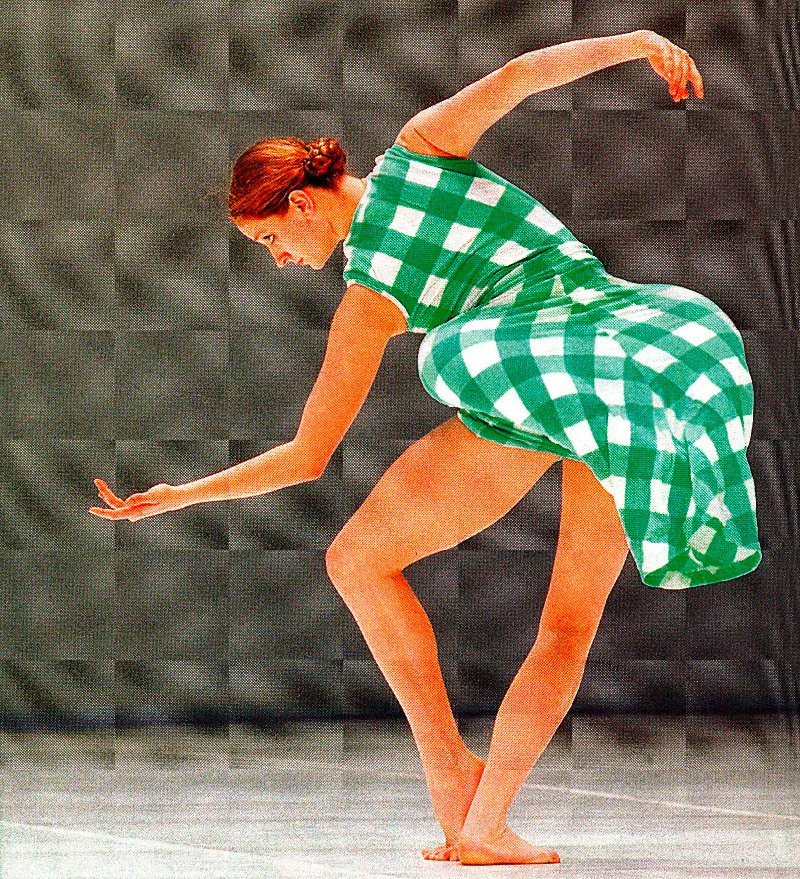

The re-enactment of a costume: “The Return of La Argentina”.

But today he thinks that perhaps his being voted Dancer of the Year was due to his development as a dancer. In 2015, he began to delve more deeply into the work of Kazuo Ohno (1906-2010), creating a solo entitled “The Return of La Argentina,” which refers to Kazuo Ohno’s 1977 signature piece “Admiring La Argentina.” This work was inspired by the Spanish/Argentinean dancer Antonia Mercé y Luque, known as La Argentina. The piece was directed by Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-1986), whose work the American choreographer has been exploring since 2013.

Model Kazuo Ohno in “Admiring La Argentina”

“Working on ‘The Return of La Argentina’ changed my way of dancing. There was a big shift in me, in terms of how I thought about dancing. I never had a role model, never had somebody I would look up to as a dancer and say: I want to dance like them – I mean philosophically.” Harrell had seen Kazuo Ohno dance twice when the latter was still alive, and it had never really affected him. But when he came across “Admiring La Argentina” in an archive in Japan, something clicked. “Admiring La Argentina – that was it. I went ‘wow,’ this is the kind of dancer I want to be. Because Butoh is not a prescription of movements, I could understand it as a way of inhabiting the mind of dancing that gave me freedom as a dancer. Maybe this change was seen on the stage.”

And so he became Dancer of the Year 2018 and in response to his nomination by the “tanz” critics’ jury for the award, he created the solo “Dancer of the Year.” The piece captures much of what makes up the art of Trajal Harrell, albeit in allusion or simply in the form of loosely associated ingredients. It is a dance born and developed from the imagination, an imagination that has been and continues to be inspired by various dance forms: American postmodern dance, voguing, Butoh, folk dances, and pop culture. The Dancer of the Year enters the stage as an old man and leaves it as an even older man. Harrell wears a mask – bent, broken, a dead or dying man, who then manages his own show on the laptop and with it his artistic life: from Butoh and back to Butoh, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. In between are the dances that have moved him and inscribed themselves on his body. They change whenever the choreographer selects a new piece of music on his laptop. From meditative oriental-style dance reminiscent of Sufi or Loïe Fuller’s serpentine movements, to disco groove, from stillness and arm dances to minimal postmodern forms, and finally to the runway walks that made him famous, but from which the dancer keeps breaking out. And for each dance, a new dress. Harrell carries them onto the stage in a huge bag and puts them on. But doesn’t wear them. Dresses are the most important props in Harrell’s art. They are changed in his shows a thousand times faster than we could ever order them online. And yet they do not end up in the Atacama Desert like the mountains of fast fashion we produce every day, but in collections in his studio in Athens, in his house in Charlottesville, in the prop room of the Schauspielhaus Zürich, where they wait to be reused on a new runway in another work. “The clothes are part of a postcolonial feminist trajectory in my work. I always paid more attention to the costumes than I did to the sets. This goes back to this idea of the operation of fashion into movement. The runway is the main form that I use in my work – that’s the signature of my work. And of course, the runway is a place where people display clothing on bodies. So we display clothing on dance. This is something that becomes a huge part of my process. At the beginning, when I’m with myself thinking about movements for a new piece I often have the clothing to help my imagination. And then as I go into the studio with the dancers the clothing is there. So from the very beginning we usually start working with the costumes.”

The solo “Dancer of the Year” was performed at the Kunsthalle Zürich in the spring of 2022 as part of a series by Trajal Harrell and the Schauspielhaus Zürich Dance Ensemble. Since 2019, Harrell has been resident director at the Schauspielhaus, which is run by Nicolas Stemann and Benjamin von Blomberg. He brought his own dance company with him and has developed a large following in Zurich. This is hardly surprising, since the Schauspielhaus Zürich Dance Ensemble embodies everything the playhouse wants to represent: diversity, gender permeability and gender performance, interdisciplinary work. The group lives out the transgression of boundaries, the coexistence of different cultures and arts, playing with identities – all of it without making proclamations or pointing fingers. “My work dealt a lot with how people perform gender. When we started this work, there wasn’t a lot of language around it. Judith Butler had written her book ‘Gender Trouble’, but expressions like non-binary, gender fluidity, these things were not used in 1999/2000. My work has been influenced by post-colonial feminist theory. I was studying women’s studies, art history, literary theory, cultural studies, and African American literature. Those things in college really had a big influence on me and this can be seen in the work. But we don’t try to educate people. I really try to make the work for everyone. Also for people that don’t believe what I believe.”

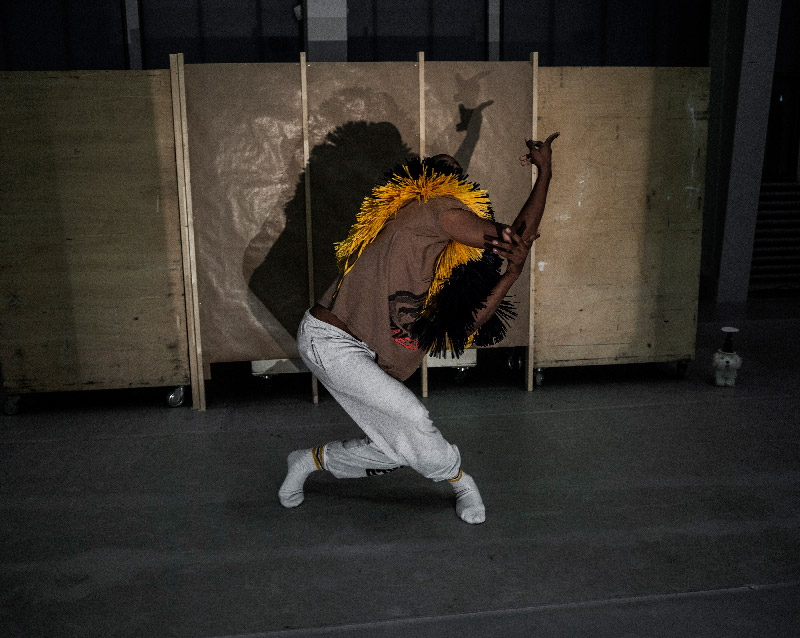

From top: Stephen Thompson, Jeremy Nedd, Alicia Aumüller

Harrell’s art has grown considerably in Zurich. He has created significant works here, including several masterpieces. Among them are “The Köln Concert,” his first work in Zurich in 2020, and “Monkey off My Back or the Cat’s Meow” from 2021, both of which can be seen at the ImPulsTanz festival in Vienna this summer, as well as “Deathbed,” the world premiere of which opened the aforementioned series of the Schauspielhaus Zürich Dance Ensemble at the Kunsthalle Zürich in spring of 2022.

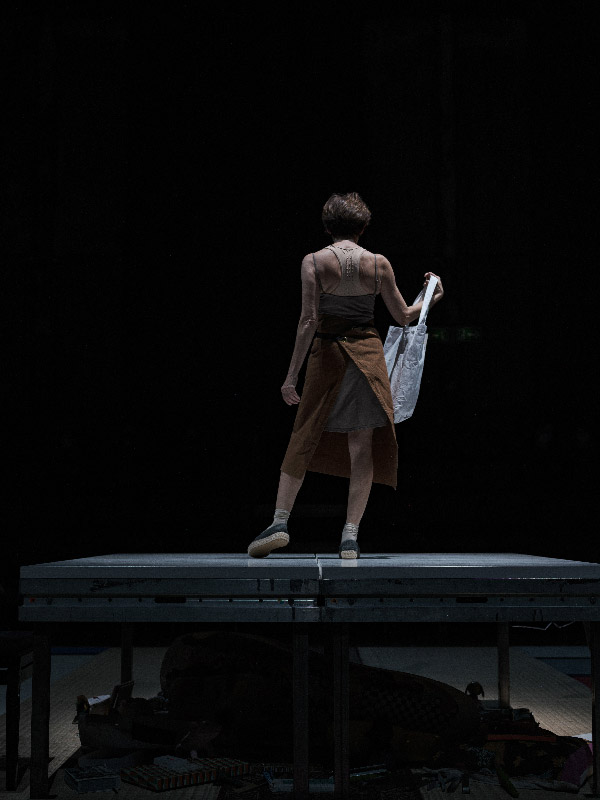

Scenes from “Deathbed,” tribute to Katherine Dunham

“Deathbed” is the last part of the “Porca Miseria” trilogy, the first part of which is “Maggie the Cat,” which will also be presented at ImPulsTanz. “Maggie the Cat” premiered in Manchester in 2019; then the COVID-19 pandemic hit and the trilogy’s conclusion had to be postponed for two years. It was shown as a whole for the first time at the Holland Festival 2022. “Maggie the Cat,” “O Medea,” and “Deathbed” are a triptych of strong female characters between conforming and breaking out: Maggie, the daughter-in-law from Tennessee Williams’ “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof”; Medea from Greek mythology; and the only non-fictional woman, Katherine Dunham, who was born in Joliet, Illinois in 1909, and died in New York in 2006.

The African-American choreographer and anthropologist is the great icon of Black American Dance. She was also an activist who went on a hunger strike to protest the deportation of Haitian detainees. Trajal Harrell visited the 96-year-old in 2006 shortly before her death, as he recalls in “Deathbed.” The feeling of not having asked the right questions never left him: Did Katherine Dunham meet Tatsumi Hijikata, the founder of Butoh, when she spent a year in Japan in 1958?

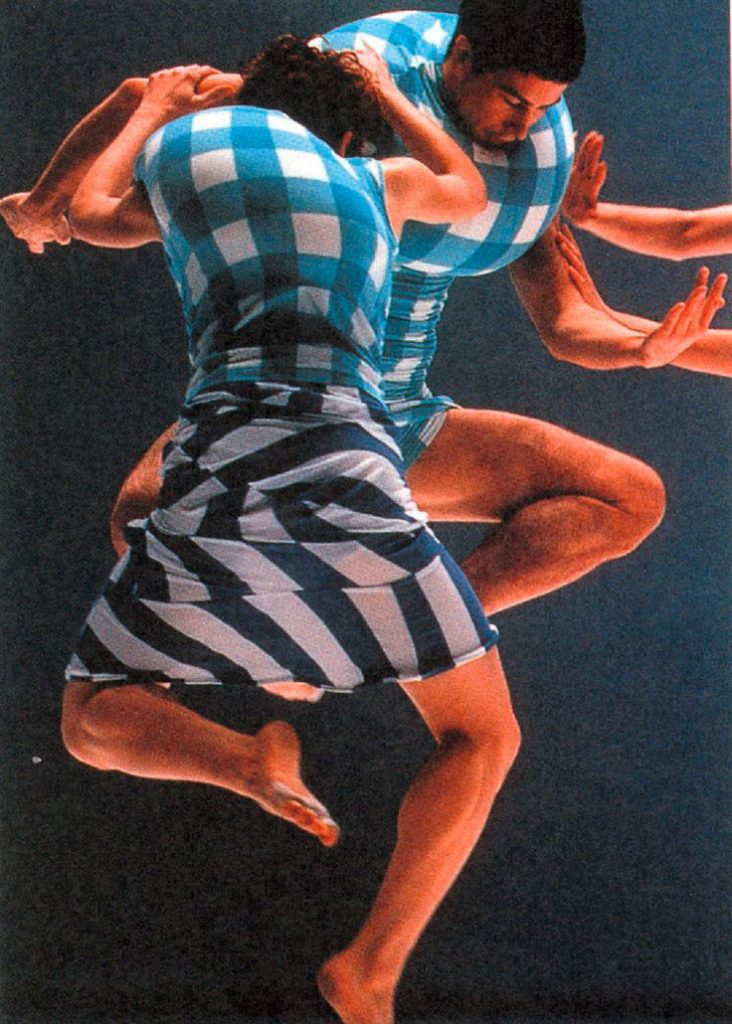

“Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at The Judson Church”

These are the questions that drive Trajal Harrell. He is a special kind of historian who researches the history of dance and finds events that never happened. He calls this “historical imagination.” He imagines encounters between protagonists from different movement schools and asks how dance historiography would have changed if the artists had actually met. In his cycle “Twenty Looks or Paris Is Burning at The Judson Church,” he asks what would have come of a connection between postmodern dance professionals and the African-American gay and transgender voguing scene. The former went down as beacons in dance history, while the latter shone only among their peers until they were brought into the spotlight by two artistic productions in 1990: the documentary “Paris Is Burning” by Jennie Livingston and Madonna’s hit “Vogue.” “Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church” refers to the title of the film and is the series that made Harrell world famous. In “Deathbed,” he inquires about an encounter between the mother of Black Dance, Katherine Dunham, and the father of Butoh, Tatsumi Hijikata. Since Harrell came across traces of the latter’s work in an archive in Japan in 2013, Butoh poses have been breaking down the beautiful appearances of his catwalks, which were never really beautiful to begin with, as they were immediately recognizable as appearances. But what effect would a meeting between Katherine Dunham and Tatsumi Hijikata have had on their respective dances? None, one had to conclude after the performance at the Kunsthalle Zürich. For many years, Trajal Harrell has been combining the catwalk steps of the beautiful and flashy from the worlds of fashion and pop with the poses of pain and terror found in the post-war Japanese dance. There is little of this in “Deathbed,” which instead features poses from Greek antiquity and steps from the Caribbean, whose local dances Katherine Dunham researched. Only at the end does one of the dancers begin to contort his limbs and face, to sink into himself, and finally be carried away under mountains of fabric. Is Katherine Dunham being carried to her grave? The icon of Black Dance is largely absent from this work, present only as a gap, a void. An open question, left unanswered by all the deceased of this world. “Deathbed” is a work about mourning, remembering, and letting go – like almost all of the pieces that Harrell has created with his Schauspielhaus Zürich Dance Ensemble.

Remembering, letting go – in “Deathbed” the performers sit in front of small tables covered with things they want to get rid of, such as perfume, cables, sponges, old dolls. In “Dancer of the Year Shop #4” from the same series, first performed in spring of 2022, Harrell offered objects from his personal collection for sale at the Kunsthalle Zürich: photos, a love letter, a laptop with personal documents, shoes, the last remaining picture of his grandmother – priced between 300 and 250,000 Swiss francs.

“What’s the value of a dancer?

Usually they sell things like pins, t-shirts or tote bags. And I wanted to amp up the level of this. If I’m going to sell as a dancer, then I’m going to sell things that are so meaningful to me that I don’t want to sell them. And I want the person buying them to take better care of them – to care for them as art objects. They were priced on emotion. These objects were part of me as the person I am and as the artist. They are part of my legacy as a dancer.”

He sold very few of them. Apparently they were too expensive for the audience who attended the exhibition. Remembering, letting go. Among the mementos was a quilt, one of only a few in the family’s possession. It dates back to the time of his slave ancestors and has been passed down from generation to generation and mended time and again.

What does Trajal Harrell know of his ancestors? Nothing.

“For many African Americans it’s very difficult to discover their family history, because there wasn’t a place where they carefully registered all the slaves. There are now ways of genetic ancestry, but they aren’t always clear records of who the slaves were, where they came from and where they went. That’s part of the brutality of slavery. My family and I, we didn’t do a DNA test to find out. And it’s not something that they talked about it because I imagined it’s something they wanted to forget over the years.”

His search for a dance of his own led him to a more recent part of the history of African-American culture and subculture: ballroom culture and voguing. Ballroom culture emerged in the 1960s when African-American and Latino homosexuals and transsexuals gathered in New York’s Harlem neighborhood for ballroom competitions. Although drag balls existed in major U.S. cities as early as the late 19th century, people of color could not win any prizes at these early balls, dominated as they were by whites. So they got together in houses and vied with one another in their voguing battles in Harlem. The houses, which bore the names of famous fashion houses, were intended to give them the recognition and protection that their families of origin often denied them at the time. It was from this scene that the dance style of voguing developed in the 1980s.

When did Trajal Harrell start voguing? Never.

“I’ve never walked in a voguing ball. I’m not a voguer.”

For many years, he attended the ballrooms regularly – not as a participant, but as an observer. The distance was always very important to him.

“That’s a big misconception of my work: that I am doing voguing. I am not, but I’ve researched voguing for many, many years. I looked at the theoretical underpinnings of voguing. I was looking at the procedures and operations, how the performativity of voguing works and applying that in the same way that I apply the theoretical underpinnings of early postmodern dance. I was not an early postmodern dancer either. In voguing, there was a procedure in which they turned fashion movement into dance. I did a similar procedure in my work looking at runway movement and turning it into dance, but only as a model of the procedure, not to create the same movements. Later in the work, we quote it and it’s obvious that we’re quoting. Quote unquote. But this is rare in my work. It’s always been my hope to honor voguing and the influence on me, but never to pretend to present it or the voguing community. This is how I show my utmost respect.”

His choreographic career began in 1999 at the Judson Church with a short piece that is almost over by the time you finish reading the title: “It is Thus From a Strange New Perspective That We Look Back on The Modernist Origins and Watch It Splintering into Endless Replication.“ The title comes from Rosalind E. Krauss’ essay “The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths.” At the time, Harrell was using resources from the Judson Dance Theater tradition, working with everyday, minimalist, vogue-inflected movements.

Harrell came to New York in 1998 to continue his dance studies. Born in Douglas, Georgia, he originally wanted to become an actor but began devoting himself entirely to dance, studying in Rhode Island, at San Francisco City College, and eventually at various schools in New York. That’s when a friend who worked for Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) took him to one of the organization’s balls.

At the time, he was in residence at New York’s Movement Research, which entitled him to give two performances at the Judson Church.

Thus was born the short piece with the long title and the surprising reaction of the audience. Trajal Harrell began to study the ballrooms more closely. The walks down the runways, imaginary and imagined real, this world of fashion, glitter and glamor, the combination of the everyday walk and the desired walk, offered him endless possibilities for movement research. The fact that the voguing movement, like the postmodern dance movement, emerged in the 1960s sparked his historical imagination: what would have happened if voguing maniacs had made their way downtown to Greenwich Village to join the Judson Church crowd?

The series “Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church” was created, with the piece “(M)imosa” touring particularly actively. (M)imosa is parody, quotation and appropriation, persiflage, drama and trash, game and lie all in one. Cecilia Bengolea, François Chaignaud, Marlene Monteiro Freitas, and Trajal Harrell sing and dance like Kate Bush, Prince, Shirley Bessie or Trajal Harrell. Then they step up to the microphone and claim to be Mimosa Ferrera. But Mimosa Ferrera does not exist – or does she?

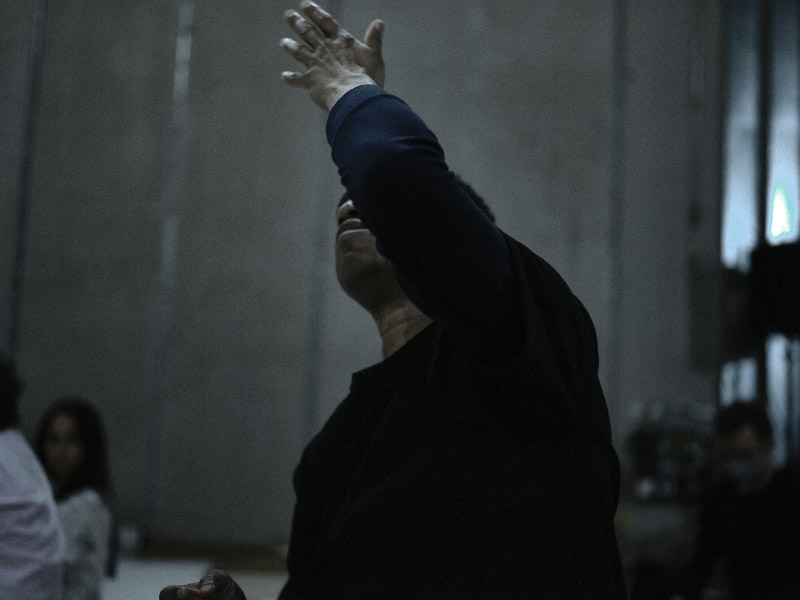

Jérôme Bel 1998

The reference is to an iconic piece of French conceptual dance from the 1990s. In “Le dernier spectacle” by Jérôme Bel, the four performers take turns claiming to be Andre Agassi, Susanne Linke, Hamlet, and Jérôme Bel. Similarly, the beginning of “Monkey off My Back or the Cat’s Meow,” which was created at Schauspielhaus Zürich in 2021, is reminiscent of both “(M)imosa” and “Le dernier spectacle.” Here, the runway goes the entire length of the shipbuilding hall as the audience on both sides prepares for the upcoming fashion show – for theater, so to speak, from Anna Wintour’s perspective. Then Trajal Harrell rises from the midst and claims to be Anna Wintour. He/she says he/she has been asked by Trajal Harrell to open the show, which she would like to do but for the fact that Harrell wants her to dance. If you are alive, you can dance. She is going to go change now. She/he leaves and actor Thomas Wodianka appears. He claims to have been asked by Anna Wintour and Trajal Harrell to open the show, which she would like to do, and so on, and so on.

The duplication is not only owed to the translation – the repetition is as much a concept as the endless walks down the runway. Again and again, the performers in “Monkey off My Back or the Cat’s Meow” make their rounds, each time wearing a new dress that is held up in front of the body as a sign that what is supposed to create something like identity here is completely replaceable – and in a flash, since it was only held up anyway. Walking on the line, legs crossing slightly so that one foot falls exactly in front of the other. Some bounce like excited ping-pong balls, others waddle like ducks or stomp defiantly – the degree of grace is negligible. Trajal Harrell’s runways play with fashion shows and the fashion world, just as they play with the spectacle of voguing. They expose the spectacle of the fashion world by hysterically subverting it, by playing with fluid – inasmuch as they are questionable – identities, juggle with the icons of dance history and pop culture. In this respect, Harrell’s dance could be read as an American answer to French conceptual dance. But unlike conceptual dance theater, unlike American postmodernist dance, Harrell’s works do not reject the spectacle; on the contrary, they return the spectacle to the stage. Albeit in a well-digested form. Fashion shows, the fashion world, and voguing are not simply quoted, just as Butoh is not simply quoted in the best of Harrell’s works, nor Loïe Fuller. The dances of the others, of predecessors and ancestors – they are assimilated and spit out as something different, something that sometimes has more, sometimes less in common with the movements of the old and the others.

Trajal Harrell began studying Butoh in 2013 during a fellowship in Japan. After the “Twenty Looks” project, he was looking for something new and wanted to delve more deeply into the fashion spectacle. He was initially inspired by the first Comme des Garçons shows by Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto in Paris in 1981. The black, asymmetrical gowns caused an outcry in the fashion press and were dubbed Hiroshima chic. Trajal Harrell noticed that the fashion press talked about the dresses in much the same way that the dance scene talked about Butoh and wondered if Rei Kawakubo was influenced by it. What if? He wanted to meet Rei Kawakubo in Japan and ask her, but then he went to the archive of Tatsumi Hijikata.

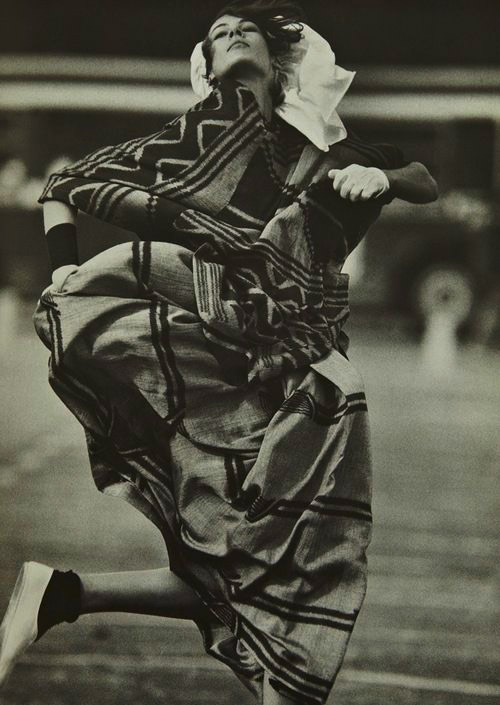

Fashion by Rei Kawakubo on the catwalk and in “Scenario” by Merce Cunningham, 1997

What followed was a world away from “Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church.” While some of the pieces in the “Twenty Looks” series came across as shrill and loud and the intention was so obvious as to be annoying at times, the works created at Schauspielhaus Zürich since 2019 are solemn and imbued with a deeply melancholic worldview. The ritual of the runway has become a ritual of mourning, the procession of the beautiful and their gorgeous clothes a funeral march.

“Juliet & Romeo”

It all started before Harrell’s time in Zurich, with the works “In the Mood for Frankie,” created in New York in 2016, and “Juliet Romeo,” created at the Munich Kammerspiele in 2017. He had brought both pieces to Zurich during his first season in 2019/20 before opening the 2020/21 season with “The Köln Concert” and presenting the new Schauspielhaus Zürich Dance Ensemble for the first time. In between, the playhouse had been closed for months; we were in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The Köln Concert” with Trajal Harrell

“The Köln Concert” was both a new beginning and a turning point. For the first time, Harrell put a piece of music at the center of a production: “The Köln Concert” by Keith Jarrett, along with four songs by Joni Mitchell. He also created an abstract choreography with his six fellow dancers, with no text, references, or images, with only seven piano benches on stage and dressed almost exclusively in black. Seven benches for seven people, with space between them. Harrell begins, sitting down on one bench and dancing with his arms. His longtime companion Ondrej Vidlar sits on another, and they both swing their arms to Joni Mitchell’s “The Last Time I Saw Richard.” Only then do the other dancers join in. Technically, “The Deathbed of Katherine Dunham,” part of the “Porca Miseria” trilogy, was scheduled for spring 2020. However, we would end up waiting for it until spring 2022. Instead, Harrell and his dancers embarked on a more COVID-19-compliant journey in 2022 and explored the music that had electrified him decades ago: Keith Jarrett’s legendary 1975 “Köln Concert.” But he had had so much respect for the music that it had taken him 20 years to dance to it in public, as he states in the program.

“The Köln Concert”

It was the reduction to the piano benches that finally encouraged him to take on the “Köln Concert.” To the fourth Mitchell song, “Both Sides Now,” Thibault Lac bobs along the runway – always on demi pointe, as if he were wearing heels. Then the famous intro sounds and now they walk in black. Or sit. They cross their legs, look lasciviously into the audience or stare stubbornly ahead. One jumps nervously across the room, another freezes in an antique pathos pose. Some get up to dance, scampering back and forth with the smallest of steps, powerful on their feet, while their upper bodies collapse in all directions – drunken Willis at dawn. The clothes stay on longer, the many colorful smarties have given way to a smart black. Was this related to COVID, as was rumored at the time? “No, no, no, the black dresses in ‘The Köln Concert’ had nothing to do with the pandemic. I found those goddess dresses ten years ago in Stockholm at a sale. And I saved them because I knew that they would be important one day. This was about Greek dancing, and those dresses were like togas almost. I wanted something that put the piece in a kind of ancient or maybe even timeless sphere. We start in a different sphere and then slowly go back and go back in time until you enter this place where the ‘Köln Concert’ happens. We change the seating and then those bodies come out and it’s in a different sphere. Those dresses are cut in a way that they can have endless shapes and silhouettes. They refer to a different time and place. Maybe it’s ancient Greece, maybe it’s ancient Rome, or some other place the viewer imagines. Again this is the historical imagination that we imagine together. This is what I work towards.”

Maximilian Reichert in “Monkey off …”

The colors return in “Monkey off My Back – or the Cat’s Meow (a piece for dancers and actors),” Harrell’s largest Zurich production to date featuring some 17 performers. Here the runway does not cross the imaginary world. It is the world. On the floor: Mondrian, oriental carpets, Japanese mats, kitsch; around them, the dancers and actors bob to a musical collage featuring songs by Nina Simone, Mia Doi Todd, Laura Nyro, Joan Armatrading, compositions by Claude Debussy and Steve Reich, among others. Some of the composite costumes reference dresses from famous fashion houses, some are just aprons, and most of them become aprons because they are not even put on, but simply held in front of the body. Collage, fake clothes, fake fashion on fake art.

The models walk along, one foot in front of the other, swaying. Some sway only with their legs, others with their whole bodies, some in high heels, others barefoot in phantom heels – a runway of zealots and the exhausted. Every now and then someone freezes in a Butoh pose. Their limbs twist, their face contorts, their mouth opens wide and ugly. One or the other lurches. One gyrates like a dervish in dusky pink tulle, others practice ports de bras and sway with outstretched arms as if held by Leonardo DiCaprio on the Titanic. About halfway through the piece, some of the performers read the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776 while the others continue to dance, on and on and ever more wildly until what is being read is drowned out by the increasing noise of the revolution, by the wild dancing and commotion. As if people here and now should not only reaffirm the Declaration, but also question it.

Alicia Aumüller

After all, it didn’t apply to everyone. Slavery was not abolished in the United States until 1865, and women did not have the right to vote until 1920. The dissenting voice rises at the end. “I had to, like open the bruise up, and let some of the blood come out to show them” – 19-year-old Daniel Hamm of the Harlem Six, on the loop of Steve Reich’s “Come Out.” To this document of racially-motivated police violence from 1966, the black-clad dancers stubbornly make their last rounds. And the minimalism, the repetition in their gait, pays homage to the beginnings of European minimalism in Belgium, where Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker created her seminal piece “Fase” set to Steve Reich’s composition in 1982.

The von Bloomberg/Stemann artistic director duo will leave the Schauspielhaus Zürich at the end of the coming season. Interim director Ulrich Khuon does not wish to continue with the Schauspielhaus Zürich Dance Ensemble. Trajal Harrell, however, would like to stay in Zurich with his people because he feels at home here, because a close community has formed around the troupe. But also because it would be difficult for him to keep pieces like “Monkey” in his repertoire as an independent dance professional. Too big, too many people, too many props. It would be a shame to lose it, because “Monkey” is a showpiece for interdisciplinary collaboration between actors and dancers. Will Harrell miss working with the actors? He hesitates. “I believe in the democracy of dance. And I’m not someone who thinks that all dance should be about the standard ideas of virtuosity. The piece ‘Monkey off my Back or the Cat’s Meow’ is a lot about issues of freedom and democracy. People feel the richness because of the different bodies they see and the different skills. If everyone was a dancer, you wouldn’t feel it the same way. But working with actors and dancers is tricky. I don’t want to make the actors seem like second class dancers. It has to be the right piece.”

“It is Thus From a Strange New Perspective That We Look Back on the Modernist Origins and Watch it Splintering Into Endless Replication”, 1999 presented as “Hoochie Koochie”

Trajal Harral in “The House of Bernarda Alba”

Most of the pieces produced at Schauspielhaus Zürich are performed by the dance ensemble. Sometimes with a single guest actor, such as Max Krause, who has already worked with Harrell in Munich and Bochum. This is also the case for “The House of Bernarda Alba” based on the tragedy by Federico García Lorca. Bernarda’s house is a women’s prison, decreed by the mother after the death of the father. Only the eldest of the five daughters is allowed to marry; the others must remain in the house and mourn for eight years. The youngest, however, gives herself to her sister’s groom and subsequently hangs herself, believing that Bernarda has shot him.

Trajal Harrell’s historical imagination has taken him – and thus us – back to the House of Dior in the 1940s. Back then, the models did not walk the runway, but swirled around in the exclusive salons within easy reach of the audience. The salon at the playhouse was recreated for an exclusive audience too. Meanwhile, Harrell does not parade the latest craze everyone is crying out for, but rather just the cry, distorted by pain and silent. The fashion is grim. Chic leather belts become dreadlocks on women and wondrous blouses turn into headscarves. Whatever splendor has found its way onto their heads and bodies pushes them to the ground.

Here, the house as an alternative family from Harlem’s voguing scene offers no protection to Bernarda and her household. The women may have a little fun with Lula Pena’s fado at first, but then Trajal Harrell enters and dances the dance of the trembling fingers. Piano and violin from Giya Kancheli’s “Time and Again” take over the sound and Butoh takes over the dance. The performers’ bodies writhe, limbs twisted inward, faces painted white, mouths contorted and drooling. Butoh, which in general was merely hinted at in the preceding works, here becomes an internal and external force at the same time – a force that drives people, not as a sign of repressed sexuality, but as change par excellence. The fashion show at Dior is not walked by the eerily sad models surrounding Bernarda Alba, but by the “petites mains,” the unsung heroines of haute couture. They present the fabrics and laces, then Bernarda’s daughters appear and transfer the elegance to the gothic scene.

“Maggie the Cat” with Helan Boyd Auerbach

The shift in focus could not be more apt. In “Maggie the Cat,” Trajal Harrell has the servants from Tennessee Williams’ drama about a phony Southern family dance. They carry various household items across the stage – comforters, pillows, dresses – while the choreographer and Perle Palombe, as Big Mama and Big Daddy, drive the action from the side. At one point, the performers walk through a box of paint, leaving brown footprints on the white floor – a footprint of African-American history, so to speak. Does Trajal Harrell want to bring to light events and things that we usually overlook?

He wants people to believe in the impossible, Harrell told London’s ‘Evening Standard’ in 2017 on the occasion of his exhibition “Hoochie Koochie” at the Barbican Gallery. What did he mean by that? The phrase did not originally come from him, but from Cuban artist Tania Bruguera – he’s referring to the oft-quoted line, “A lot of people know it’s impossible … but the impossible is only impossible until somebody makes it possible.”

“I heard Tania Bruguera say that her work was about the impossible. And it made me think, Yes, this is what we can do as artists. I don’t think art is everything. If you get cancer, you need a doctor. But art can make you believe that one day we could solve cancer. Humanity needs to believe in things. Like, I didn’t know that we could ever live in a world where we begin to question genders in the way that we do now, that we make possibilities for the re-thinking of gender all in the way that we do now. There are many things like that. Art is able to get into our nervous system in a way that shakes up our rational brains, shakes and changes our senses, so that we think things that we possibly didn’t know and we begin to believe in things we don’t have language for. This is what I think art can do: make us believe in the impossible. Right now we have to believe that there is an end to this war, even if we cannot fathom how it will happen. I’m always looking at impossibilities in my work. ‘The Romeo’ is one of them. It is an impossibility.” As Harrell explains in a QA flyer distributed to the audience before the performance, his latest Zurich work “The Romeo” is a vision of a universal dance passed down through generations by families and friends. Anyone can dance this dance, although it may change over time and in different contexts. Just ask your neighbors or relatives, and maybe they’ll show you. “The Romeo” has become a simple dance, simpler than many of the dances from the previous pieces. And it is considerably more joyful than the funeral marches on the runway in “Monkey off my Back …,” “Deathbed,” and in the salon of Bernarda Alba’s house. “’The Romeo’ has travelled through the world and it’s a complete fabrication. But we get on this line together and people are touched and they believe in something. And we take this feeling into the world and that may change us and give people the energy to do something. That’s my little part. That’s what I can do as an artist.” What’s next? Besides gender issues and the legacy of colonialism, what issues burn Harrell’s feet so much that he wants to bring them to the stage? Weakness. “I’m interested in weakness. This has come from my research into Butoh. How do we represent weakness? How do we represent the weak, how do we represent the vulnerable? And I don’t mean just vulnerability of feeling. I mean people who are weak and don’t have all the capacity to get through suffering. I’m trying to make space for that in my dancing. So much in dance is about strength and showing how strong you are or how well you do something. What happens when you have to show your weakness? This is what interests me now.”