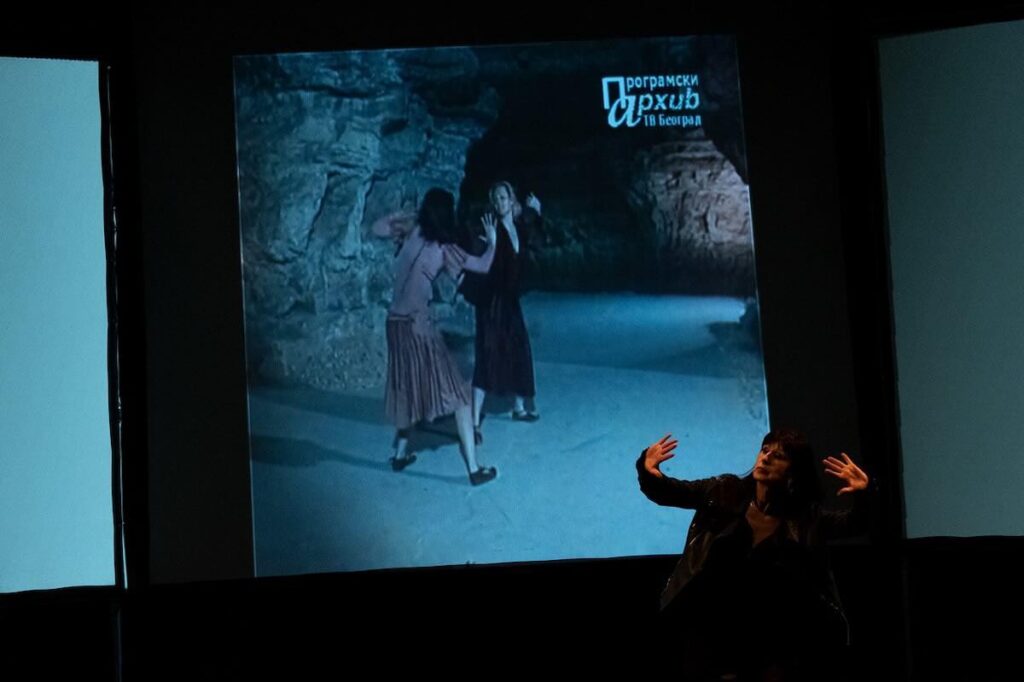

Koruga says: “We have no stars. We don’t have artistic public figures who perform at public events and from time to time express their personal views or opinions that others might share. But for me, the people in our show are all stars because they are contemporary witnesses, because in their heyday, often at the beginning of their careers in the 1980s, they worked with the major cultural figures of the time. They worked closely with choreographers and directors such as Petar Slaj, Nada Kokotović, Ljubiša Ristić … They also worked for the stars of folk and pop culture, for Lepa Brena, Usnija Redžepova, Vesna Zmijanac, Zdravko Čolić, Josipa Lisac … At that time, there was still recognition, they won prizes and the Signum dance company was even given a military plane by the presidency to fly them to Mexico to show their award-winning piece ‘Bernarda Alba’s House’. They played in Russia in front of Gorbachev, and it wasn’t just a pop star like Lepa Brena who was able to do this.” Koruga is on fire at this point, his enthusiasm is huge. He wants to give dance, the art of movement, the same dignity that is otherwise only given to actors, directors, writers, painters and athletes. Why is the dance scene in the background at all? Koruga sees one reason in the way dance was perceived by other artistic disciplines. In Serbia, the highest form of dance education until 2014 was the secondary ballet school, a secondary school diploma. Even today, there is still no state higher education institution for dance.