War and lechery continue to play leading roles on the world’s stage. It is thus not only to be tolerated, but to be hoped that theatre makers will continue to treat these subjects tragically or comically or critically on the world’s stages.

Wonge Bergmann

That is exactly what Jan Fabre did in his 2015 magnum opus, “Mount Olympus—To glorify the cult of tragedy (a 24-hour performance),” and what he has done time and again over the course of a 40-year career, in which he has come to be regarded as one of the “Great European Stage Directors” (Vol. 8 of Bloomsbury Publishing’s series of this name, released just last year, focusses on Fabre alongside Pina Bausch and Romeo Castelluci).

This hero of the theatre, however, suffered a rapid fall from grace in the wake of an open letter published by 20 dancers from Fabre’s Antwerp-based company Troubleyn,. Jan Fabre, as few others in the world of contemporary dance, has had a fair chance to do his work. More fundamentally, life is not fair—neither for heroes nor their victims, neither for the weak nor the strong, neither for the rich nor the poor. We are here in the logic of tragedy, not justice; in the logic of power, not ideals. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to take another close look at Fabre’s “Mount Olympus”—precisely in the context of me, too.

We like to hold artists to a higher ethical standard than warriors and politicians and similar men. I say men because the kind of hero we are criticizing—one who conquers our enemies and our hearts—is in most cases of the male sex; and the virtue of disciplined violence in the service of an indomitable will, required of this kind of hero, is associated with popular albeit outdated notions of masculinity.

In an upside-down post-modern world, we like to think artists can critically embody the brutal ethics of flesh and blood heroes on-stage while revealing themselves to be ideal officers and gentlemen off-stage (in other times it was just the opposite: the hero was supposed to be delicate of feeling on stage and ruthless in everyday life). No doubt there are exceptional artists—and exceptional generals—who through force of character or fortunate circumstances appear consistently as decent, honorable men.

But the qualities required of a choreographer and stage director share a large set of common terms with those required of a warrior and general, and similar relationships of power and dependence arise (although by no means inevitably) in the contexts of war and theatre. Further, the human body, male and female—its powers and its limits and its frailty—is at the heart of both spheres of action.

Fabre’s warrior of beauty

Thus, when it appears that relationships behind the scenes at Troubleyn reflected, to some extent, the egotistical brutality of the power struggles and sexual predation we saw on-stage in “Mount Olympus,” we should hardly be shocked.

Jan Fabre’s modus operandi as an artist was provocation, you might even say cruelty. He abused and insulted his dancers, pushed them up to and beyond their limits, both physical and emotional—perhaps also occasionally treated them with an extraordinary tenderness that only served to set them up for the next slap in the face or buttocks. As a lover, it would seem his techniques or predilections included aggressive sexual predation. (I take the dancers’ accusations about all this at face value not because I can confirm their truth from personal experience—I have never met either Jan Fabre or any of his dancers—but because I recognize the technique from having witnessed or experienced it at the hands of other teachers, choreographers, directors, bosses and politicians.)

Provocation does produce reactions, for better or for worse. For the past 40 years, Fabre has been provoking both dancers and audiences to anger and tears—sometimes maybe even in stupid ways. But just provoking people to disagree is a valuable contribution to society. And we should not be too quick to conclude that Fabre’s mission and tactics were fundamentally worthless all along and feel sorry for those (dancers) who were complicit in the Troubleyn undertaking. Painful, yes—without question. But any dancer or actress or employee or wife who sees herself as the victim of a mean and overpowering man is bound to stay that way. To be free she must see herself as free. And anyone who took part in “Mount Olympus” has every right to see herself (or himself) as a free actor, with her own strengths and virtues and weaknesses, making the best of her fate with independent choices and discipline and effort—while also making an important contribution to an artistic project that was meaningful to a wide audience.

Those dancers who stuck around for a while did so, one would hope, because they were learning something in the process. When a critic (or choreographer or boss) tears your work apart, you are likely to learn more than when he praises it. The only time a person learns nothing is when he gets no honest feedback on his work at all, or shuts his ears to it because it is too painful to his own ego.

This does not mean that Fabre’s dancers should continue to put up with his abuse. They shouldn’t. They should walk away. And they should feel free to talk about their experiences, good and bad, in public and in private. If a crime was committed, the victim and the state have a right to prosecute it. The definition of the crime should not be unduly expanded, however, insofar as it involves the freedom of speech. No one should be put in jail—or silenced (how?)—for making sexist remarks, any more than they should be silenced or put in jail for criticizing government economic policy or police brutality.

The authors of the Open Letter acknowledge the defense that dancers were always free to walk away and look for another job. They argue that this is too high a price for a dancer who has trained for ten years and then finally landed a steady job to pay. But one dancer quitting will not bring about the downfall of someone she views as a sexist pig. The status quo has its momentum. No one dancer ought to have the power to brand and ruin a director. If everyone agrees he is a pig, the momentum will shift and a movement will occur, as it did with the publication of the dancers’ open letter in Rekto:Verso. What is more essential is that each individual dancer need put up with a choreographer only as long as she chooses to.

A second open letter that appeared shortly after publication of the Troubleyn dancers’ letter, and in the same medium, takes a position that undermines the liberty of everyone working in dance. Signed by 126 choreographers eager to prove they are on the right side of things by ostracizing Jan Fabre, the letter boldly asserts that the goal is “creating a space where all are free to create without fear, pain and humiliation.” If that is what you want, just take Prozac and stay at home. But for the benefit of an audience that finds Prozac scarier than reality, it is fortunate there are still dancers willing to take a degree of pain or even abuse in order to put something on stage which sheds a brutal light on the way human beings in fact exploit the Earth’s resources and one another on a daily basis—to gain a profit, gain a victory, or just get their rocks off.

Merel Severs, Kasper Vandenberghe with Andrew Van Ostade, Sarah Lutz

Among other vaguely formulated good intentions, the choreographers’ statement also claims: “We are open to the idea that decisions around the support that artists receive should factor in considerations of ethical practice.” That sounds harmless enough, but we should be careful what we wish for. Fact is, the ethical values of the dominant class holding political power already play a big role in defining artistic content by virtue of the power that class wield in distributing support for the arts. Insofar as one of art’s functions is to give a voice to those on the fringe, and specifically to those who pose a threat to the “dominant culture”—whether because they are too politically correct or too little politically correct—the last thing we want is to give the state and its courts yet more power than they already have to decide what art works do or do not get produced.

The person or agency that has the power to allocate funding will always play an important role in shaping artistic content through the power of selection; but in the first and final analysis it is up to dancers to decide with their own bodies whose artistic vision they support. And it is ultimately in their own interest to take responsibility for how much lechery or verbal abuse they tolerate before quitting. This is not blaming; it is empowering her.

In the case of Fabre, I for one am grateful to the dancers who put up with whatever they put up with for as long as they did in order to bring “Mount Olympus” to fruition on stage. Regardless of the circumstances under which it was created, Fabre was able—on the eve of his downfall—to create one last magnum opus that drew upon decades of thinking about the theatre and eloquently addressed the tensions between heroes and common men; men and women; safety and thrill, danger and boredom; ecstasy and pain; time and infinity; repetition and change and renewal.

In light of the dancers’ open letter, it is also worthwhile to ponder how “Mount Olympus” addressed two topics central to the me-too debate: Institutional power, i.e., personal power reinforced by the concentrated resources of an institution, however it may be funded; and the “rape culture,” i.e., a culture in which sexual predation by men—and in its extreme form violent rape—is normalized or even idealized. (One may well object that the term “culture of male sexual predation” would be more accurate, as applied broadly to our European and American culture; but the prevalent term “rape culture” has the advantage of being clear and provocative.)

Those approaching the matter from a feminist-political perspective will no doubt be disappointed that “Mount Olympus” does not more clearly point the way out of this mess; but should anyone be in need of further evidence that the culture of classical Athens (as transmitted by the extant tragedies) or of contemporary Europe is a “rape culture,” “Mount Olympus” provides it in aces and spades. Sexuality is here consistently presented as a raw power struggle, often a physical one, and men are everywhere seen to use their power to obtain sexual satisfaction—from other men or women. The work by no means prettifies, or portrays as harmless, or apologizes for this brutality. On the contrary, we are consistently allowed to identify with the victim. We feel her pain. The great strength of the work, and its power to provoke reflection in the context of the me-too debate, lies in the fact that it requires us to acknowledge the humanity—sometimes even the charm and beauty, the amoral vitality—of the heroes or perpetrators at the same time.

It is interesting to note that Angelica Liddell, in “You are my Destiny (lo stupro di Lucrezia),” in the same year as “Mount Olympus” addressed the role that female fantasies, no less than male fantasies, play in producing our “rape culture.” In “You are my destiny,” the choreographer and principal performer Liddell muses that her rapist was “the only one willing to lose everything for a moment of love.”

Like war and violence or implied violence, rape and rape culture are presented in “Mount Olympus” unflinchingly as a part of life in 5th century B.C. Athens and the 21st century, and the work makes it clear that this violence is not the exclusive province of a minority of rude foreigners in a faraway land (Persia or Syria); but that it forms an integral part (fuel or by-product) of our lives as consumers and citizens of “civilized” colonial powers like Greece or Belgium or Germany and the U.S.

All of us face various uses and abuses of power in our daily lives; in the theatre, for instance, power relations will always arise when choreographers obtain funding to hire dancers. All these situations potentially involve sexuality, because sexuality forms an essential part of our identities and interactions with other people. And this is particularly true in a medium like the dance, involving precisely the exploration and exploitation of our bodies.

Nor is the influence of power on our sexuality a one-way street, to the exclusive advantage of one sex or class. Sexuality often confers a special kind and degree of power precisely on the “weaker” sex. Moreover, sexuality—and specifically extra-marital sexuality—is a profoundly threatening and de-stabilizing force, closely linked to other forms of criticism against the dominant power structures of society. For all these reasons, a fair amount of freedom and the concomittant acceptance of individual responsibility for the risks relative to sexual practice among adults, as well as its depiction in art, is essential to protect us all from the evil of moral conformism enforced by state violence (e.g., the official suppression of homosexuality)—which is no less harmful to our liberty than the failure to penalize rape.

Few works of theatre have addressed all these questions as deeply as “Mount Olympus”, which may never again see the stage—in part because of Fabre’s downfall and in part because mounting it takes so much commitment and—yes—suffering on the part of the dancers. Let me therefore reprint here what one audience member (what I) saw at the world premiere of “Mount Olympus.”

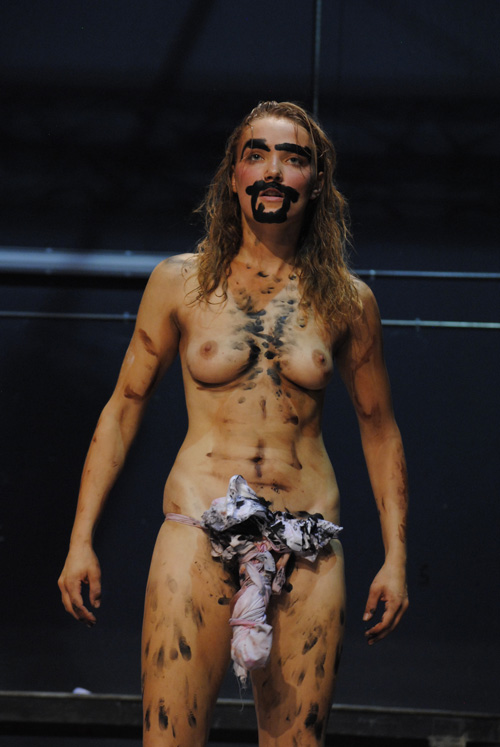

a bacchante

The premiere of “Mount Olympus” at the Foreign Affairs Festival in Berlin on 27-28 June 2015 was, by any measure, a great experience. But great experiences do not just feel especially good. They hurt. They can kill. This goes, in differing degrees, for experiences in bed, in battle, off stage, on stage, and in the audience. The word “great” (to the extent it implies that big things are also noble, superior, stirring, magnanimous, deep, consequential)—or perhaps rather the values of people who use it as a term of praise—has for this reason been drawn into question time and again.

Jan Fabre, in a work that at long last accords to the body—viz. to the dance—the primary place in our experience of tragedy that it always occupies in love and war off-stage, and did occupy on-stage at the Festivals of Dionysos in 5th-century Athens two-and-a-half millennia ago, questioningly treats heroes and greatness and violence and humanity so thoroughly that no one who witnessed and survived the production will ever again be able to think about tragedy without recalling it, or experience tragedy without remembering it.

“Mount Olympus” must be regarded as Fabre’s magnum opus and one of the outstanding theatrical achievements of the early 21st century. It evinces a lifetime of thinking about the Greeks and the origins of tragedy; a lifetime of thinking about the body and the stage. But it also has everything to do with life in the 21st century. And in light of recent history—no less than the ancient—one may well be excused for believing that the question with regard to greatness is not how much good it does the world, but how little harm.

α

In the plays of Sophocles and Aeschylos, the heroes have flaws—particularly hubris—and they suffer and die on account of those flaws as well as the arbitrary exercise of divine power. But Prometheus in Aeschylos’ play never loses our sympathy—he remains mankind’s savior. And even Ajax—a man who vows to kill his own allies after seeing his personal honor slighted, and then kills himself in mortification not from remorse at this plot but from embarrassment at having let Athena trick him into slaughtering sheep instead, like a fool—even Ajax earns a great deal of sympathy from us as portrayed by Sophocles. It is only Euripides who portrays gods and heroes—I won’t say unsympathetically, but in such a way that we must ask ourselves: good grief, can’t we do without them? all these self-styled gods and heroes who so upset the lives of regular people in their maniacal pursuit of wealth and honor?

Hitler and Stalin are always cited as the ultima ratio proving that mankind needs heroes to combat its vilains. But both Hitler and Eisenhower, both Stalin and McCarthy, ultimately derive their power from the same source: your abdication of responsibility for yourself. It would be better if each of us found a quantum of heroism inside us—be it only sufficient to die free—and thus collectively did without the heroic savior who blames a vilain for our unhappiness and promises to bring back the halcyon days.

And when the government of Indonesia in 2015, 50 years after one of those bonfires of humanity competing for the distinction of second most horrendous genocide of the 20th century, goes on referring to the men who carried out the sadistic killings of “communists” as “heroes,” we may object that this is a misuse of the word hero. (See Ian Buruma on Beauty is a Wound and The Act of Killing in “The Violent Mysteries of Indonesia,” New York Review of Books, October 22, 2015, p.60.) We may wish to suggest the word “hero,” and the property of “greatness,” can better be applied to a different kind of hero, one modeled on Euripides’ Menoeceus and Iphigenia, butonly stronger and more mature, with humanist rather than patriotic values, at once more subjective and more universal. The real heroes are Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Ghandi, Jesus Christ—or Socrates who, while the Peloponnesian War was raging, walked around Athens trying to persuade people that man’s highest goal was not “the great,” but simply “the good.” No matter how much we admire a Socrates, a Jesus, a Ghandi, however, we know there is a little Ajax screaming out in pain inside every one of us. And suspect that if we actually succeeded in fulfilling our Socratic, humane ideals, we might no longer be human.

Fabre addresses these issues head on in “Mount Olympus.” He goes a long way towards demonstrating that any value judgment of heroes’ motives remains subjective. While some heroes may act on the basis of motivations and ideals we approve of more strongly than others, the essence of heroism is not a lofty goal, but the willingness, maybe even the thirst, to maim and kill in order to achieve it. Heroes are not paradigms of moral courage; they are leaders or loners, whether in war, politics, business, or the arts. They are excessively human, egotistical creatures, driven to glory and ruin by their excessive passions. What makes them heroes is Dionysian rage. And Fabre compels us to concede that there is something loveable, something beautiful, about heroes nonetheless.

Cédric Charron

β

“Mount Olympus” encompasses, to an astonishing extent, the entire corpus of surviving Attic tragedy, insofar as it focusses on the legends and heroes (primarily about the House of Cadmus, the House of Atreus, and the Trojan War) through whom the epic bards of the Greek Dark Ages (ca. BC 1200 – 800) kept alive the memory of the historical Trojan War and the demise of the great Greek kingdoms of the Mycenaean Era. These legends formed, several centuries later, in the period from the Persian to the Peloponnesian Wars the material for most of the plays of Aeschylos, Sophocles, and Euripides.

It is nevertheless the lens of Euripides, with his profound questioning of the nature of the hero, which is indispensable to “Mount Olympus”—although Euripides by no means has the last word. One can even see a deep parallel between this mature work of Jan Fabre and the very last play of Euripides: The Bacchae, which in a way—even at its posthumous premiere in BC 406-05, just months before Athens lost the remains of its navy and capitulated to the Lacedaemonian alliance—already incorporated by reference the whole history of the classical period of Attic tragedy.

“Mount Olympus” is plainly meta-theatre in a way that The Bacchae of Euripides are not, or need not be. It is quite possible to read and perform The Bacchae focusing on its plot of the revenge that a jealous god takes upon non-believers and particularly the royal house of Thebes (Cadmus and his daughters). The play gains impact from its foreshadowing of Sophocles’ most famous trilogy—Cadmus is the grandfather of Oedipus; and from the observation that Bacchus or Dionysos, who plays an ungenerous part in this play, is not just an over-sexed, haughty young god with a chip on his shoulder, but the godfather of all dance and theatre (most of the surviving tragedies were premiered at an event called the Festival and on a stage called the Theatre of Dionysos).

In “Mount Olympus” the very subject of the work is the nature of the hero, the nature of tragic theatre—understood by Fabre, as it was by the Greeks, to be dance theatre. The stories of the individual characters from Greek saga and mythology who appear on stage—Eteocles, Odysseus, Hecuba, Oedipus, Jocasta, Pentheus, Phaedra, Hippolytus, Alcestis, Hercules, Agamemnon, Electra, Orestes, Medea, Antigone, Ajax, Philoctetes, and a few others—play a crucial but supporting role in the play. The real question addressed is one leitmotif of Euripides’ late drama: why in the world do we need (and love) heroes? Why do we need (and love) Dionysos, and tragedy? What is extraordinary about “Mount Olympus”—why it may well have few parallels in the history of post-Vietnam, post-heroic, post-modern meta-theatre—is that it also succeeds in being theatre, and extraordinary theatre at that.

The plot of “Mount Olympus” thus reads rather like the summary of a modern treatise on the nature of tragedy:

The hero, i.e. the ideal, abstract, notion of a still human superman who does and experiences great and horrible things on behalf of us in the chorus and audience, does great things (i.e. horrible things to the bad guys) not, as in Aeschylos or Sophocles, because he is driven to pursue an other-worldly vision of honor and beauty and fairness, but rather—as in Euripides—quite plainly because of his primal, childish, egotistical pursuit of wealth and honor. The difference (to Euripides) is that the heroes in “Mount Olympus” do not try to hide their egotistical motives beneath specious, hypocritical rhetoric, which the playwright allows us to see through. They frankly admit as much.

The hero does horrible things to his own team-mates and brings about his own downfall not because he is unwilling to compromise or submit to an unjust higher power (as in Aeschylos’ Prometheus Bound), not by mistake (as in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex), or because the gods are as cruel and vain as the heroes (as in Euripides’ The Bacchae), but as it were promiscuously—just because it is in the nature of the hero to kill and maim and penetrate, and the hero is beyond good and evil. Drawing towards the end of “Mount Olympus” the most obvious conclusion from the heroic bloodbath to which we have been exposed, first Ajax (grippingly played by Pietro Quadrino) and then the chorus ask the audience rhetorically; “does the word hero make you sick yet?” These first two movements, going a step beyond even Euripides, set up the critique of heroes we would expect from a post-Vietnam, feminist, queer, post-colonial, or generally post-modern analysis.

The hero is rehabilitated by pulling the rug out from beneath his accuser, the chorus. You do, don’t you (says the hero to the chorus) belong to a so-called democracy and you did vote, didn’t you (directly or indirectly), to send me to war (against Persia, Japan, Germany, Sparta, Syracuse, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, whatever) in order “to protect your economic interests abroad?” (On this phrase, see below.) And you now expect me to act like a lap dog in a china shop, kissing ass to some wheedling politician who claims he owns the china I brought back from the war in Japan and pretending I have only ever acted to defend the noble cause of justice and human decency? Well, fuck you. I tortured and killed, I was tortured and all but killed; and all for your economic well-being. I am boss here and you have got to take me for what I am—a raging, blood-drunk animal with the power of life and death over you.

Kasper Vandenberghe, Merel Severs

This is a liberal summary of the other speech that Ajax gives in Chapter 13 of “Mount Olympus.” In Fabre’s condensed version of Sophocles, Ajax argues that the victorious warrior (himself), and not the wheedling politician (Odysseus in Sophocles), should have been given highest honors and authority (the armor of Achilles in Sophocles). He then slits the throats of the entire chorus (of his fellow countrymen) on stage, one by one, sparing only the last victim, for whom he substitutes himself. Fabre leaves out the madness and the sheep introduced by Athena, focusing again on the hot-blooded but clear-headed brutality of the hero.

This movement corresponds to Nietzsche’s critique of Euripides in The Birth of Tragedy and more generally to his defense of our Dionysian nature and the gloriously thoughtless superman inspired by mythological—not rational—ideals. With the tremendous difference that Nietzsche holds the horde of “bourgeois mediocrity”—the cringing, helpless, fearful chorus of normal people who just want a quiet pleasant life—in unmitigated contempt (see ch. 11 of Die Geburt der Tragödie). Nietzsche would sweep aside (how, one dares not speculate) modern man—with his urban habitat and effete dependency on technology—to make room for a renaissance of the German Volk of yore, as known to us through the Germanic sagas that form the basis of Wagner’s operas. Nietzsche regards as an admirable criminal the passive, ironic, thoughtful, analytical Socrates looking on critically from the audience (id., chs. 12-15). With his insistence on reason and understanding (Nietzsche claims), Socrates killed myth and initiated the long, slow suffocation of man’s Dionysian (instinctual) nature.

Nietzsche’s lens is as essential to “Mount Olympus” as Euripides’. After Euripides has de-mystified the hero, we need Nietzsche to remind us what attracted us (and Homer and Pindar and Sophocles) to him in the first place. After Euripides has turned Dionysos into a kind of divine monster—if also a charming, sophisticated and even effeminate one—we need Nietzsche to remind us what a crucial part that god, or his attributes, continue to play in the genesis of human creativity, not to mention procreation.

Nietzsche, at least by implication, also forces the thinker, the observer, the philosopher to look critically in the mirror and ask just what he has done to help realize the better world he has imagined. Nietzsche reminds us of the damning contrast which the Greek language made between word and deed (best translated as “walk the walk, don’t just talk the talk”). His anti-intellectual ruminations remind us that doing is much dirtier than thinking; that the scientific, objective perspective is also an escape from subjective responsibility; that perfect objectivity means becoming a robot—a creature of man that is not just heartless, but ultimately also weaker and less intelligent than its creator.

But Nietzsche swings too far back in his defense of the self-centered superman—well beyond Aeschylos, for instance, whose Agamemnon is no pure ideal of manly virtue. And he fails to make a crucial distinction between the mythological “Volk” and the hero—he seems to believe that the Volk of yore was made up entirely of heroes. Whereas all of Greek tragedy—not just Euripides—and even Homer provide eloquent testimony to the timeless struggle between the claims of society and the claims of a few extraordinary individuals.

Finally, one must perhaps take a full step back to see the absurdity of Nietzsche’s claim that it was Socrates’ overly analytic mind that was responsible for the downfall of Attic (and all human!) culture. Was it not rather the greed and pride (of both leaders and citizens), which catapulted the Athenians into the Peloponnesian War and made them keep doubling the stakes over a period of 27 years rather than fold and mourn and regroup? For all his emphasis on heroes and practical action, Nietzsche never once mentions the Peloponnesian War in his treatment of Euripides and Socrates in the Birth of Tragedy.

Jan Fabre, while paying due tribute to Nietzsche’s analytical (sic) insights, does not repeat Nietzsche’s error. “Mount Olympus,” while pulling the rug out from beneath the chorus—showing that they, too, are as hypocritical as the politicians they vote for and revile and ultimately as egotistical as the heroes they fear and love, just weaker—does not thereby ennoble the heroes who take a larger share of responsibility for good and evil in the world. We in the audience cannot take sides with either the passively suffering chorus or the actively raging and suffering hero—we hold out in hopes there is some solution to the riddle that will allow us to take happiness into our own hands and do away with heroism and suffering. Nevertheless, we feel sympathy for both (chorus and hero); we sense that we are a part of both, or that a part of us is hero, a part of us chorus. We are all human and all suffer together. Just heroes more than the rest of us.

And Fabre does not give in to the allure of a primordial golden age, does not long for an atavistic rebirth of mythological men and values, as Nietzsche does. Fabre’s heroes may hearken back to mythological times; but they have their feet firmly planted in the 21st century. Indeed, that is one of the great achievements of “Mount Olympus”: to show that the Greek tragedies, and the mythological figures that people them, are not merely interesting in a historical or metaphorical sense. They are, as characters, alive and well and living amongst us in Berlin, New York, Antwerp, Rome, and even Athens in the 21st century.

The fourth movement of “Mount Olympus” is easy to describe and could easily (or facilely) be said to apply to all tragedy: the sum of the horrible things the hero does to the bad guys (who maybe weren’t so bad after all) plus the horrible things the hero is compelled by nature and his character to do to himself and his own (who maybe weren’t so good after all) equals beauty, to the extent those great and horrible deeds are acted out on stage in what Nietzsche would call apollonian form for the purpose of enlightening mankind rather than in “real life” for the purpose of acquiring worldly wealth and honor.

That this movement is easy to describe and subject to widespread consensus, however, does not mean it is easy to achieve or even grasp. We have at this point in “Mount Olympus” (as generally in Euripides, too) been exposed for 24 hours to an unrelenting stream of obscene, vulgar, cruel, ugly, and self-serving or self-destructive behavior by god and hero and chorus alike.

Yet here and there throughout and overwhelmingly in the last scene, where the entire cast of dancers pair up on stage and heap paint and slander and abuse on themselves and their mates for the umpteenth time, the whole stage is transformed into a glorious, colorful canvas of sweating, screaming, spasming human bodies, and tears of joy come to your eyes.

The stage is suddenly beautiful, simply beautiful. It shouldn’t be, you tell yourself. What they just went through, what I just saw, was awful, and it still hurts. And yet it is beautiful, you can’t help the feeling. And that is the nature of tragedy.

Cédric Charron

But then, the lack of mathematical clarity in this function:

together with an intuitive doubt buried somewhere deep in your heart, makes you question whether this fourth movement is a movement at all. Is this bloodbath really beautiful only because it is transformed by theatre into an edifying experience? Or is that explanation not rather something like religion, a reassuring lie which the weak at heart repeat to themselves in order to make life, or tragic theatre, bearable?

The identity of the question of theatre with the question of religion seems hardly worth contesting. The hard part is whether the edifying nature of religion and tragedy amounts to the hard-won triumph of faith over resignation, or the comfortable triumph of self-delusion over harsh truth. I wouldn’t dare propose an answer to this conundrum; but I wondered to my own horror, watching “Mount Olympus,” whether the bloodbath was not (meant to be) just beautiful without reference to any edifying or cathartic effect of theatre, without indeed any distinction between theatre and reality: wasn’t the bloodbath just in and of and for itself beautiful? Can in any part of life a bloodbath, by dint of the rage and passion, the will to life and power, the need to do, not just observe, and to change, not just be, which it expresses—can that bloodbath be not just ugly, but ugly and beautiful both? Maybe that is the nature of tragedy, and our attraction to it.

There will never be a definitive answer to the question of whether theatre simply mirrors life, or transforms it into something better (if the play is a tragedy) or worse (if it is a comedy) than life (Aristotle, Poetics 1448 A). But it would seem that Fabre views theatre as equivalent to religion, and that he is at least tempted by the more humane conclusion that we bring tragedy and tragic heroes on stage precisely because they are fundamentally different and better than reality and real-life heroes—and as such can edify us. This is evident from a sign standing in the lobby on that path in and out of the theatre we all traversed repeatedly in the course of 24 hours:

I—and I expect my experience is shared by a large fraction of that ultimately small number of people who saw “Mount Olympus” premiere in Berlin or who will see it in the course of the eight or twelve performances this event will likely ever receive in its complete, 24-hour form—I am still walking around, three months after the curtain finally fell, in that state of nervous erection common to infatuation and trauma, with a delicate stomach, tense muscles, tired brain and generally heightened physical awareness, i.e. in withdrawal from, or rather still impaired by the state of Dionysian ecstasy into which I was drawn as a mere spectator to the grand and awful events that “Mount Olympus” brought to life on stage. This comes partly from a humbled feeling of gratitude for the superhuman acts of the dancers on stage, of Jan Fabre and all his collaborators; partly from anger at those same performers for bringing so much pain onto stage for no other purpose apparently than to assuage it again through their beauty and commitment and self-sacrifice; and partly from the inexplicable, unspeakable and almost guilty confession that I secretly go on wishing to identify with the bad guys—with the heroes—on what the Greeks called the orchestra (dancing place), rather than bear passive witness to the grand spectacle of life from the chorus or audience or reading chair.

γ

That “Mount Olympus” could not only keep the audience’s attention more or less continuously for 24 hours, but even as it were draw us into the Dionysian train to Cithaeron and keep us wandering there for months, even after the god had left us, owes to the fact that this performance succeeded on so many different levels.

Fabre’s strategy for achieving catharsis was to expose us relentlessly in the most realistic terms possible to uninhibited violent and sexual self-expression. The action on stage thus often had a palpable physical and emotional effect on the audience. Between the donning and doffing of togas, the slinging, pointing, or rubbing of various organs and weapons, the excess of blood and dirt and sweat and tears, the stage felt like it was constantly tottering, from beginning to end, over the abyss of camp, porn, or even snuff (there were moments when the action on stage was almost unbearable to watch). What allowed us to gain this insight into our own libido, without being swallowed up by it, was Fabre’s equally relentless shifting of perspective and sympathy.

Porn works through a bias of the camera catering to the sexual perspective of its intended audience. It caters to our fantasy (culturally sanctioned in men) that the object of our desire wants, more than anything else in the world, exactly what we want to give her—even when what we want to give her involves action that is self-aggrandizing and degrading or painful or harmful to her. Fabre never allowed us to wallow in that fantasy. He invariably jolted us out of it by forcing us to identify with the object as well as the subject, by turning the tables, or by driving the subject to the point of pain as well, as often happens when in our Dionysian rage we lose control—as often happens when we actually have sex with a real person. The result was therefore painful insight, not orgasm.

On the historical and intellectual level, the lewd, obscene humor that pervades “Mount Olympus” seems to refer, not so much to Attic comedy, as to the satyr plays which preceded the development of both comedy and tragedy in Greece. There is much evidence for the conclusion that Greek tragedy (literally “goat dance”) originated in what was essentially a dance form, the dithyramb, and thus descends more distantly from the dances in Dionysiac fertility rituals. Dance remained an important element in the production of tragedies throughout the classical era. Sophocles even wrote a lost treatise on the use of chorus and dance for the stage. “Mount Olympus” persuasively illustrates this connection.

And without raising the moot question of authenticity—of how closely the mixture actually resembles 5th-century Athenian theatre—“Mount Olympus” also provided a persuasive illustration of how the antics of a dancing, chanting chorus can be apposed to heroic monologue so as to form an overwhelmingly powerful unity. “Mount Olympus” likewise incorporates naturally the elements of dialogue, song, visual representation, and movement—the genres of art, spoken theatre, opera and dance theatre—to create a spectacle that goes a long way toward correcting our contemporary experience of Greek tragedy as a primarily dramatic or even literary form. No doubt Fabre gives dance or physical theatre greater precedence over dialogue than 5th-century Athenians did—but the resulting work of total theatre is very likely closer (in its length, as well) to what Athenians experienced at the City Dionysia than any production of a single play from a trilogy that does not use music or dance, or uses it only as a diversion.

“Mount Olympus” draws in historical detail to add depth to the layer on which it is a portrait of 5th-century Athenian culture. For instance, a speech that Dionysos recites twice (“I will teach you men not to come”) does not refer to any tragedy I know; but may well refer to the tradition that the City Dionysia were established to appease Dionysos after he sent a plague affecting the male genitalia upon the Athenians. It further manages—through the meta-plot described in part II above—to make a coherent contribution to the theory of theatre; but does so in such a way that the theoretical lens only strengthens the dramatic impact of the work. Fabre can only refer, of course, to a non-fluid medium such as vase painting or stone sculpture

Merel Severs

But it is interesting what seeing a human sculpture on stage does—precisely to our perception of time. And the section called “Greek Statues: male/shemale” does more than slow theatrical time down almost to a stop. The eight male nudes in a semi-circular frieze modulate from male to female with beguiling effectiveness by tucking it between their legs and assuming a new pose; this sculptural interlude thus makes a strong statement about the plasticity of our perceptions of gender, too.

Melissa Guerin Torres

The fluidity of gender definitions in the other direction is treated just as thoroughly and emphasized—as in Euripides—by the plethora of female characters whose Dionysian rage drives them to acts every bit as bloody and violent as the men’s: Medea, Hecuba, Clytemnestra, Agave; without, however, treating them as shallow monsters.

As a matter of course, “Mount Olympus” brings in references to contemporary (21st century) culture and events through subtle modifications to Euripidean and Sophoclean monologues. But more broadly, the movement or action—as opposed to speech—on stage is rooted firmly in the 21st century. Among other things, Fabre brings the body language of the urban fitness gym, the discotheque, maybe even reality television on stage—without breaking the tragic, historical form. He draws upon a tremendous range of characters from Greek legend to create a portrait, both distillation and composite, of the Greek hero and his relationship to god and chorus, while at the same time using carefully selected and edited speeches from the Greek tragedies to bring this abstraction to life like a Proteus constantly squirming and changing shape to elude stating the truth.

δ

A drill sergeant (Gustav Koenigs) leads a company of about ten dancers in a question-and-answer work-out chant whose rhythm and melody you know from every movie about boot camp, or perhaps from boot camp, if you have been to one (I haven’t ).

Gustav Koenigs

The words they chant have a touch of vulgarity, but also a touch of the oracular:

What is the pain that hurts the most? The blade of a sword or the words of a ghost.

What is the shame you can’t deny? The thighs of your mother or your father’s eye.

What is the fear that haunts the night? The demons of sleep or the dreams that have died.

What is the monster that eats the day? Unused talents and hair turning grey.

The dancers are skipping rope in time, except that the rope is a heavy chain, whose loud thud striking the stage floor drives home the work they are doing. The foregoing is a complete and unabridged description of the action on stage—for the next 30 minutes. The dancers keep chanting the same four verses, keep skipping rope (with individuals increasing the pace to double time now and again) to the point of utter exhaustion. Long after your heart has burst, sitting in the audience, the dancers sit and—eat an ice lolly.

For me, watching them eat an ice lolly was as painful as anything else in “Mount Olympus.” My body was screaming out for water—for them. Like children or drug addicts, they instead abandon their bodies and their health to the short-lived pleasure of an ice lolly. And then get up and jump rope for ten more minutes!

“Mount Olympus” will bring home the theme of Dionysian excess time and again in the form of a killing rage or sexual pleasure—for instance in a scene (ch. 3) in which the dancers, men and women, rub themselves on plants for a painfully long time, as in a self-destructive masturbatory trance induced by crystal methamphetamine.

Matteo Sedda

The fascination with pleasure drugs and addiction is treated explicitly in chapter 8, “Dionysos’ alchemists lab.” But the banal and ostensibly healthy context of extended rope-skipping, in which anyone who has once tried to exercise can identify with the dancers, brings home as powerfully as any blood bath the feeling of pushing or exceeding limits.

Formally, chapter 1 of “Mount Olympus” works like a paradigm of theatrical minimalism, in the sense of the minimalist, gargantuan sculptures at Storm King, or Philip Glass at his best: one short movement sequence, drawn from everyday life, repeated with shifting dynamics to the point where it takes on new layers of meaning, compelling the audience to feel empathy with the panting dancers. And this as integral part of what can only be called a maximalist orgy of blood and guts. The chapter also makes a statement about the nature of the classical hero—for unlike the fat overseer brandishing a whip whom you sometimes meet with in post-classical times, it was the drill sergeant who lasted longest of all skipping rope—thus reinforcing his claim to be leader and hero.

This hero then delivers a monologue on the sacrifices that will be necessary in the coming civil war. “The enemy is within us … the time has come … we must all die for victory.” We already knew from the rope-skipping and chant that the hero was preparing the chorus for war. We now get it spelled out—and then some. Through the physical preparation for and initial part of his speech, we are drawn into sympathy with his, with their cause. We all know there have been times when citizens feel, rightly or wrongly, that they must defend their homes against a foreign invader or even choose sides in a civil war. Which all sounds noble and heroic—until the words “we all must die for victory.” Fabre has set us up to understand the utter absurdity of war, by first getting us to identify with the warrior.

This epiphany, like the force of the entire scene, is fully legible to someone with no specialized knowledge of dance or Greek history or tragedy. But it certainly gains redoubled force when you realize the hero who is speaking is Eteocles, encouraging the citizens of Thebes to defend the city against his elder brother Polyneices, who is asserting a valid claim to share the throne their father Oedipus had bequeathed to them both. It could have been an American officer mobilizing native forces in Afghanistan, it could have been an Athenian orator motivating midshipmen to join the expedition against Sicily; but he is called Eteocles, and his speech is drawn from Aeschylos’ Seven against Thebes.

In sum, Fabre moves assuredly between history and the present day, the Greeks and the Europeans, mythology and aesthetics, theory and theatre, minimalism and brutalism, opera and art and dance and drama. He exhibits artifacts of tragedy that remain recognizable in their provenance, while being incorporated into an utterly original vision that lends them new meaning—much as Euripides did when he (following Stesichorus) first excoriated the figure of Helen of Troy in The Trojan Women (BC 415) and then, just two or three years later, reinstated her virtue by having her translated miraculously to Egypt and giving Paris an illusion to take in her place to Troy (Electra, lines 1281-83; and Helen); or when he re-cast the legend of Hercules murdering his family as the result of divine caprice cruelly repaying a life of heroism, rather than as the original sin which the hero dutifully sought to expiate through his labors on behalf of civilization.

ε

Above all, perhaps, “Mount Olympus” succeeds on the level of performance. Great dancers and great choreographers may not always need each other; but they often do attract each other. Balanchine indeed saw training great dancers as the central pillar of his work. In “Mount Olympus,” the awe which the dancers inspire in us has little to do with their accomplishment in the technique of classical or modern dance—though they show that, too, at times.

It is nonetheless virtuosity, a virtuosity based on endurance, range, and also specific skills. Chapter 2 of “Mount Olympus” opens with a virtuoso piece of classical acting, as Hecuba (Anny Czupper), the mater dolorosa of Greek tragedy, pleads eloquently but in vain with an impassive Odysseus to end the cycle of violence and sacrifice.

This speech is followed by a chorus that brings the audience to share Hecuba’s unspeakable grief by meta-verbal means. About twelve dancers, initially standing in a line across the stage and speaking softly, repeat one phrase: “no. no. fuck. fuck. take me” over and over again.

The phrase never entirely loses its erotic overtones, but from the emphasis on “me” in “take me” you soon realize the words express the first three stages of grief (Kübler-Ross)—denial, anger, and bargaining—with the stages of depression and acceptance being left unexpressed. The line breaks up as the volume and emotional intensity of the paroxysm increase. Soon the stage is churning with bodies receding and coming forward again in a competition for the attention of some unseen (and non-responsive) divine savior. “No, take me (and not my daughter/son/husband/dignity),” they shout—as Hecuba also says in the play of Euripides. The volume and intensity ebb and flow, with the exhausted dancers ultimately collapsing together again into a single line and quieter emotional state after a solid 15 minutes of screaming “take me.” Thus acceptance may ultimately be achieved through the fact of their exhaustion, though they never state it outright.

I could not without writing a book do justice to all the extraordinary performances that went into “Mount Olympus.” Whether in a lengthy monologue on ripping out your own organs through the vagina to give the phallus access to your heart;

Ivana Jozić as Jocasta

in a literal (physical) battle of the sexes lubricated by olive oil

or the lewd, exuberant cross between Saturday Night Fever and rave party with split-jumps and hand-springs that opened and closed the show; the dancers/actors performed at a stunning level of virtuosity and endurance with countless shifts of mood and tempo and countless premature climaxes for a period of 24 hours, doing things which appeared, and no doubt often were for them, ugly and painful.

It would be hard to overestimate the degree of trust and commitment which Fabre elicited from them, and which they brought to us, in order to create this unique work of theatre. They pushed their bodies beyond all conceivable limits, as in war, to produce an effect which may, through the mysterious transformation of theatre, have ultimately yielded beauty; but which in its immediate impact was much more obviously harmful and degrading.

Sleeplessness—or rather the wickedly productive state of sleep deprivation praised and cursed by warriors and artists beset by Dionysos—was the subject of a text repeated twice (like several other discrete thematic elements of the production) during the day and night of “Mount Olympus”.

Foregoing sleep, at least for one weekend, was required of everyone involved in this production, not least of all the audience. At times, I thought of the army messenger from Euripides’ Phoenician Women reporting on the battle of Eteocles and Polyneices: “we who were watching sweated more than they, fearing for our friends” (tr.: Elizabeth Wyckoff, Euripides V, line 1387). But the performers in “Mount Olympus” not only forewent sleep, they danced and screamed and fucked and fought for 24 hours. What sleep the dancers got between Saturday and Sunday they got in sleeping bags on stage. And so I was curious enough to watch them sleep for the second half of the 90-minute nap they were granted between 5:30 and 7 am (I had slept earlier); and in particular to see the transition from sleeping time to waking time on stage.

The wake-up call was provided by the ghost of Clytemnestra (Ivana Jozic again), who walks among the sleeping bags, as among tombstones in a cemetery at night, exhorting the performers with increasing bile and outrage to stop wasting their time and hers in slothful sleep.

Early in the morning: The ghost of Klytaimnestra (Ivana Jozić) wakes up the theater.

She has been murdered by her children; her soul cannot rest until she obtains revenge. So wake up, you lazy cowards, wake up and avenge my foul murder! Again, Fabre presents us with a wicked and spiteful creature who nevertheless manages to win our sympathy, even in this prologue to Fabre’s rendition of the myth-chronologically antecedent action of Iphigenia at Aulis and the Oresteia.

Thus there were at least 27 virtuoso performances given in “Mount Olympus,” and many more backstage or in the period of preparation for the event. But one performer has to be singled out by virtue both of his role in “Mount Olympus” and of how he played it. Andrew van Ostade as Dionysos, who in his all-too-human thirst for revenge and satisfaction continuously goads his mortal victims on to push their self-liberation all the way to the extreme of self-mutilation (or vice versa), maintains throughout a certain divine aloofness while also exhibiting a perverse, boyish, Caravaggian glee in exciting his victims to a self-destructive excess (of exercise, violence, intoxication, or orgasm). He can shake and shimmy the rolls of fat in his stomach in triumph; roll them in seduction; or brandish them as a weapon in threat. In speech, his high voice modulates whimsically between joy and anger, flattery and scorn, threat and seduction. And he plays virtuosically on giant “tympana” (hand drums), as Dionysos must, using an imperious ictus in a shifting meter ornamented by syncopation and tonal coloring to draw his victims on stage and in the audience into an ecstatic frenzy. No one who saw Van Ostade as Dionysos will ever be able to picture the god any other way.

Andrew Van Ostade

ζ

The Bacchae of Euripides dramatize the story, part legend and part history, of how the cult of the nature-god Bacchus entered, or re-entered, the Greek mainland in the Dark Ages in the early part of the first millennium BC. After meeting with violent resistance from many Greek kings, Dionysos was gradually incorporated into the Greek pantheon as the god of wine and ecstasy and dance theatre. In its earlier, pre-institutional form, however, there is strong evidence that the cult of Dionysos incorporated many of the most disturbing elements played out dramatically in “Mount Olympus” and gruesomely depicted in words in Euripides’ play—including hunting with bare hands, tearing apart alive, and eating raw small animals of the woods, in order to partake of the god’s divinity through eating the flesh of the animals briefly representing him. A historic basis for even the element of human sacrifice, to which Euripides refers with his graphic description of how Pentheus is maimed and killed by a band of women in Bacchic frenzy led by his own mother and aunts, can by no means be ruled out. No matter how gruesome you find the actions on stage in “Mount Olympus,” your experience pales by comparison with actual participation in a Bacchic ritual in 10th century B.C. Thrace.

Marc Moon van Overmeir

Euripides’ play focusses on the stand-off between Dionysos and a legendary king, Pentheus, who challenges Dionysos’ claim to divinity and tries to ban his cult as morally reprehensible. Dionysos capitalizes on Pentheus’ own prurient fantasies, enticing him to spy on the Bacchic women’s orgy, only to turn him over to them for mutilation because he has profaned their ritual. In his exasperation with god and man at the end of the Peloponnesian War and at the end of his life, Euripides portrays both antagonists (who are first cousins through their mothers) as young, impetuous, haughty, and spiteful, though in very different ways. The decisive difference between them is not what Arrowsmith aptly calls Dionysos’ “smiling, soft-spoken, feline effortlessness” in contrast with Pentheus’ stiff machismo, but quite simply the advantages that immortality and divine parentage confer on the god.

In earlier plays, Euripides often contrasts the peaceful ecstasy enjoyed by the followers of Dionysos with the homicidal rage of Ares and other gods. In Heracles (ca. 420), a goddess called Madness—at the behest of Hera and as she claims against her own will—drives Hercules to murder his wife and children (“Mount Olympus,” ch. 7).

The Chorus lament:

Now the dance begins! Not here,

the drums! no lovely thyrsos here! …

No wine of Dionysos here!

And in a play as late as the Phoenician Women (BC 410):

Ares … lover of blood and death,

… why stand away from [Bacchus’] feasts …

[to pursue your] dance that knows no music?

It is generally Apollo, not Dionysos, whom Euripides attacks in his plays. As Emily Townsend Vermeule put it in one of the best sentences I have ever read about Euripides: “Electra is another phase in [Euripides’] campaign against Apollo, the morality of the gods, and tender-minded human champions of ‘justice’—a concept in fact cold and difficult, admirable in the abstract, ugly in concrete situations.” In The Bacchae, Dionysos does not merely get his fair share of the blame for human folly: he has come to incorporate the passions of all the inhabitants of Mt. Olympus (and the Earth). He has, as Tiresias states explicitly in the play: “usurped even the functions of warlike Ares.” The Bacchae, the god’s band of women followers,

swooped down upon the herds of cattle

grazing there on the green of the meadow. And then

you could have seen a single woman with bare hands

tear a fat calf, still bellowing with fright,

in two, while others clawed the heifers to pieces.

There were ribs and cloven hooves scattered everywhere,

and scraps smeared with blood hung from the fir trees.

They then move to the farmers’ village:

Everything in sight they pillaged and destroyed.

They snatched the children from their homes.

When the villagers try to defend themselves:

the men’s spears were pointed and sharp, and yet

drew no blood, whereas the wands the [Bacchante] women threw

inflicted wounds.

And when Pentheus later tries to spy on them, his own mother tears him apart alive, limb for limb, and impales his head on a wand for a trophy.

The chorus of Bacchae claim that Bacchus “loves the goddess Peace.” He gives “to rich and poor … the gladness of the grape” and “doubly” blesses him

whose simple wisdom shuns the thoughts

of proud, uncommon men and all

their god-encroaching dreams.

Thus it would seem that Bacchus spares the meek and those who drink themselves into oblivion. But in fact no one is spared in this perhaps bleakest of all Euripidean tragedies. Pentheus’ mother, Agave, is mortified when she learns that in her Bacchic frenzy she has murdered her own son. It is insinuated that Tiresias is only promoting the cult of Dionysos for his private, pecuniary gain as priest; and that Cadmus, the retired king and grandfather of both Pentheus and Dionysos, has honored the god only as a precautionary measure, currying favor with a half-divine grandson he recognizes to be more powerful than himself. The Bacchae’s Dionysos does not distinguish between followers and victims. All are punished when the god reveals himself.

Fabre uses the Bacchae in two ways in “Mount Olympus.” They are specifically treated in one of the 14 approximately 2-hour-long “chapters” into which the work is divided, each chapter oriented around a figure or group of figures from Greek legend and the surviving play or plays devoted to them. The Bacchae chapter of “Mount Olympus” presents the main characters in a speech in which Pentheus pledges to root out the immoral Bacchic cult that has led the women of Thebes astray; in Agave’s speech of triumph while exhibiting the severed head of her son, which in her frenzy she still believes is a mountain lion’s cub; and in a speech of Dionysos (drawn from the speech of a messenger from Cithaeron in Euripides) describing the scene of the hunt. This chapter also includes several non-verbal scenes addressing other themes of the Bacchae: laughter, wine, ecstatic dance, and transgender and autoerotic yearnings.

The latter are present in Euripides, too, through the women who leave their looms and babies at home to go hunting; cross-dressing by all three male figures in the play (not just by the actors, in Euripides’ day always numbering three men who cross-dressed whenever a woman appears on stage); and Pentheus peeping on what he hopes will be a lesbian orgy. The mortal characters of Euripides’ Bacchae at the end must acknowledge Dionysos as all-powerful god; but they have learned to hate him at the same time. In its final ode, the chorus reflects on the unpredictability of the gods. Fabre, in a surprising but characteristic turn of mood, ends this chapter of “Mount Olympus” with one of the few moments of released tension in the day, with Mozart’s “Ruhe Sanft.”

But “Mount Olympus” in its entirety can also be viewed—like The Bacchae of Euripides on an allegorical level—as a direct treatment of the conflict between man’s animal nature (represented by Dionysos standing in for all the gods, for fate and necessity, for chaos, for appetite and instinct) and man’s striving for civilization—in the sense of self-restraint and order and mastery of nature (Nietzsche’s apollonian principle). Dionysos is inside every one of us. He is the volcanic eruption of nature’s primitive, aimless power in man, which apollonian discipline can hope to modestly influence the course of, but never truly “channel” or suppress. Far more overtly than in Euripides, and here fully in keeping with Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, “Mount Olympus” shows that this struggle between urge and restraint is the fundamental subject of tragic theatre: theatre is man’s attempt to sublimate experience; to channel our Dionysian impulses into Apollonian form.

The men and women on stage are fully under the influence of Dionysos, so that the arguments in favor of self-restraint and civilization generally remain unspoken. Fabre knows that the bloody excess, the cruelty and self-destructive actions on stage will evoke these arguments automatically from his audience. But at times they are given voice on stage, as well. Hecuba in chapter 2 is the first to do so, in her plea to Odysseus to spare her daughter’s life and end the cycle of violence. The second, more ambivalently, is Pentheus in his speech promising all good citizens of Thebes that he will rid the town of the lewd, uncivilized, and destructive cult of Dionysos that has seized its women like an illness.

While the stand-off between Dionysos and Pentheus and even to a remarkable degree the words of their speeches are drawn directly from Euripides, Fabre makes significant modifications to their characters. In lieu of Euripides’ inexperienced, impudent and reckless young king, Fabre (and performer Marc Moon Van Overmeir) portrays Pentheus as a seasoned, hard-working leader, albeit one with a pronounced inclination to authoritarianism. Pentheus’ speech is a good example of how the authors, with tremendous restraint and effect, adapted a relatively small number of lengthy speeches from classical tragedy to sketch out both characters and meta-plot in “Mount Olympus.”

The speech begins in “Mount Olympus,” as in the Bacchae, with the sentence “I happened to be out of town … but reports reached me of some strange mischief here.” If I remember correctly, however, the authors/editors of Fabre’s texts for “Mount Olympus” added here, where I place the ellipsis, the phrase “working hard and risking my life to protect your economic interests abroad.” This interpolation (in Overmeir’s cogent delivery) characterizes Pentheus as a seasoned, confident leader; ties him in to the other heroes of “Mount Olympus,” suggesting he was off waging war on behalf of the city; and in particular suggests he was off waging war for our economic benefit. The addition is fully in keeping with Euripides’ style—a blasé confession of realpolitik by a politician. It spells out an argument central to both Euripides and “Mount Olympus”—that heroes act for wealth or honor. And it makes Pentheus absolutely fit for the 21st century, without vitiating the character as developed by Euripides.

This one phrase allows us to see Pentheus as a business leader, as well as an Aeschylean warrior/ Euripidean politician / hero. What Fabre is focusing on in “Mount Olympus” is power, specifically male power. And that power is expressed in Europe and America today no less in the board rooms of banks and multi-national corporations than in the corridors of government or the battlefield. The close ties between merchants or bankers or land-owners on the one hand and warriors and princes on the other goes back to time immemorial. Consider Aeschylos’ metaphor for war as the “money-changer of bodies” (in Agamemnon). Think of the Venetian Empire, the Dutch Empire, the British Empire—first came the trade routes, then the navy to defend them. The phrase may even refer to a German president, Horst Köhler, who in 2010 resigned after being criticized for suggesting publicly that Germany should wage war when necessary to protect trade routes.

The salient feature of the bond between war and money in the late 20th and early 21st century is perhaps not its unusual strength and resilience, but its near invisibility. The division of labor between professional soldier and professional banker is so complete, the distance between boardroom power centers and oilfields and battlefields is so great, that we actually need someone like Jan Fabre to remind us of their unity of purpose more than ever before. We need him to remind us that the wars being fought around the globe from Vietnam to Afghanistan to Syria and the Sudan are being fought, with real blood, directly or indirectly, in large part for our economic (not our human) interests.

Thus the character of Pentheus in “Mount Olympus,” as a hero/king invoking the safety, morality, and economic well-being of his people while incidentally magnifying his own public image, is utterly convincing, utterly contemporary, and even appealing in a way. We may quibble that Pentheus goes too far in the direction of authoritarian repression of individual liberty; but the conduct exhibited by those under the sway of Dionysos could scarcely be tolerated by any political leader, no matter how liberal, and scarcely be condoned by any moralist other than one who owns an S&M club. As portrayed in “Mount Olympus,” Dionysos’ victims really are hurting each other and themselves.

On the level of language and speech-acting, too: the monologues in “Mount Olympus” (dialogues in the narrow sense are rare), while preserving the lofty tone of classical tragedy, display a succinct, matter-of-fact diction and realpolitik sensibility that sound perfectly at home in the 21st century. Another of Fabre’s subtle interpolations in this same speech of Pentheus is the sentence: “sometimes freedom requires a policeman on every corner to protect people from themselves.” This does everything mentioned above and even adds a dose of biting Euripidean humor.

Fabre does something similar for all the characters of Greek drama who appear in the course of “Mount Olympus.” The heroes are stripped of any claim they may have had to moral high ground or nobility of purpose in the plays of Aeschylos and Sophocles; but also of the cowardice and hypocrisy Euripides would have layered them with. We are left with raw, naked heroes, who rape and kill and sacrifice their own health in a monomaniacal pursuit of honor and satisfaction restrained only by other heroes or their own mortality. We cannot help but feel sympathy for men, like Ajax, who have committed horrible “crimes” and ruined themselves while or after fighting our enemies. We may wish they could defeat our enemies and then learn to exercise the values of restraint, humility and forgiveness preached by Socrates or Jesus Christ. But we recognize that Socrates and Ajax are incompatible types. Ajax kills our enemies for us and expects only honor and obedience from us in return. Socrates lets himself be killed rather than killing in breach of his values. Which leaves us alone to die with him as martyrs. Socrates expects every one of us to be as brave as Socrates in the face of death. Few of us are.

Anthony Rizzi

In the last scene before the finale, in a stunning performance by Cédric Charron, Fabre’s version of Philoctetes appears before us to explain how he has been utterly broken—turned into a woman by brutal sodomization, maimed and crippled and stripped of all strength and dignity (“I have nothing left to offer but my wound”)—i.e., transformed from hero into victim by the tides of war. We know perfectly well (after seeing this play, if not before) that it is “fair” for the hero who lived by the sword to die by the sword; but we all feel his pain nonetheless. We feel it only vicariously—which is quite different from actually feeling what he feels, mainly in the magnitude of pain. But this leads us all the more ineluctably to recognize that we owe the hero a certain debt in suffering as he does to spare us the inconvenience of fighting ourselves. We love him, love his greater courage, love the part of us that he stands for, standing there, suffering unspeakably, speaking to us.

“Mount Olympus” shows we are all—for all our varying degrees of strength and all our varying appetites—ultimately animals subject to the urges and instincts of nature; we are all the victims of Dionysos. We need not capitulate unscrupulously to those urges and instincts; but we ought—given we are anyway powerless to suppress them completely—to see the beauty of violent instinct as well as of staid reason and moderation.

We may be able to mitigate the pain of living by not striving to be a hero, and paying as little heed as possible to those who do—assuming we have had the good fortune to be born in 1969 in Edmonds, Washington, and not in Aleppo or the Gaza Strip, circa 1990 or 1890. But this may well amount to a cop-out; an act of cowardice rather than a Socratic act of passive resistance. After all, Socrates and Jesus Christ, two prominent models of anti-heroism, both died heroically as martyrs. The Near and Middle East (and not only these) are just overflowing with heroes and victims right now, including a significant number that are members of the US Army, Air Force, CIA, or Presidential Joint Special Operations Committee. A lot of others buy weapons from U.S. and German manufacturers with foreign aid money originally collected from taxpayers in Edmonds, Washington.

Maybe there really is no escape from the tragic arena, regardless how we interact with heroes and heroism, Dionysos and the will to power. We can fight the heroes, we can hide behind them, we can talk to them, we can make love to them; but we cannot just leave them in peace and think we are doing good. Like the Euripidean Bacchae, then, the meta-Bacchae that is “Mount Olympus” ends with an acknowledgment that the hero, the tragic movement, our Dionysian nature is all-powerful and enchanting, but also loathsome. As in Euripides, Dionysos moreover makes clear at the end of “Mount Olympus” that this—this 24-hour-long bloodbath evoking the entirety of Greek mythological history and much real history, too—was “only the beginning.” The suffering and blood will continue to flow.

While Euripides, in the last words of his last tragedy, has the chorus reflect rather aimlessly on the unpredictability and amorality of the gods, “Mount Olympus” ends with a terse invocation to aesthetic, physical renewal in the utopian space of the theatre:

Take the power back.

Enjoy your own tragedy.

Breathe, just breathe,

And imagine something new.

Fabre is not just rehabilitating the hero. He is asking us all to imagine, and try to be, a different kind of hero. It is just possible he wants us all to become dancers. As we have seen, that won’t be a piece of cake.

Fabre the man, it seems, failed to achieve in the alchemy of theatre the transformation from Ajax to Socrates, hero to anti-hero, ladies’ man to lover. But he did succeed in producing a powerful testimony to his struggle, while catching a select but sizeable group of dancers, theatre-people, and audience members up in the dionysian train—to the enrichment of all. All this is unlikely to reverse the crash landing of Fabre’s career in the theatre; but if seeing or participating in Mount Olympus helps a few of us avoid the hypocrisy of shouting “for I am holier than thou,” it will have had an enduring impact for the good.